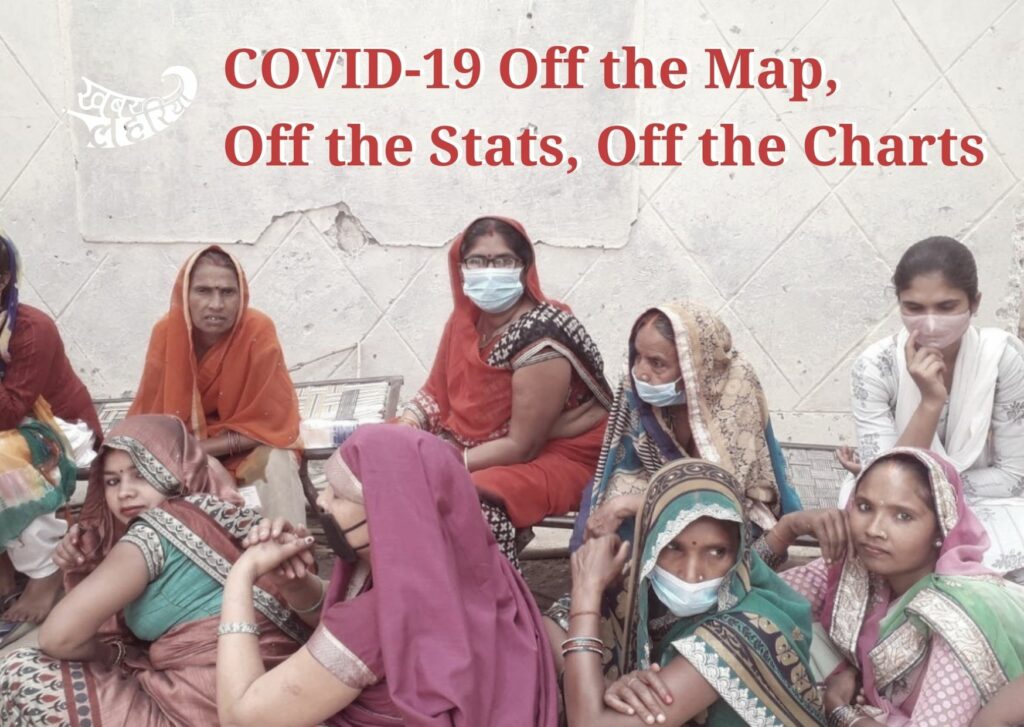

The Multiple, Horrific Ways in which the Pandemic’s Second Wave is Decimating the Northern Rural Hinterland

Banda, Uttar Pradesh: “At least one person in every household here is extremely unwell.” Shivdevi, seasoned Khabar Lahariya reporter with over a decade’s experience, a resident of Bhavanipur village from district Banda, shares pandemic status that is perhaps very similar, if not exactly alike, the situation in urban, middle class India. COVID 19 might be the greatest equalizer we’ve witnessed in our world of haves and have-nots, but what Shivdevi shares next, highlights how this is a most peculiar situation, specific to the rural hinterlands of northern India. “Not one person here knows or cares or believes in corona.”

While that statement might sound flippant to those of us busy isolating and/or mobilizing resources over Twitter, it is, in fact, layered with the multiple, horrific truth that is life in rural U.P. Speaking of structural and systemic failures that have over the decades, crystallized into the very culture of rural life, it also indicates the sheer disconnect between geographies – what some call Bharat & India.

This is what the Switzerland-based NGO ACT Alliance refers to in its India report, in its cited claim of medical experts that India’s COVID19 numbers are even higher with many cases not reported from rural areas. Claims supported by a recent article culling together nation-wide ground-level reporting. Which Dr. Prabhat Jha of the University of Toronto sums up simply, in this report, “The biggest gap is what’s going on in rural India.”

M.I.A. Awareness Drives: First Wave, Second Wave, Same Same but Different

When the first wave of the pandemic hit India in 2020, rural U.P. remained largely unaffected in terms of actual illness and/or death. The severe lockdown put into place, as a measure against the spread, forcing reverse migration, had been the most damaging aspect for people living in these geographies, since they comprise the estimated 400 million informal labour force who mostly subsist on daily wages. In fact, at one point last year, India held the dubious, unenviable tag of being the only country where the number of reported deaths attributed to lockdown measures (suicide, police brutality, hunger, exhaustion) was higher than the number of deaths attributed to a coronavirus infection. “As Aravind Yadav said in this KL

report, his rage at the abandonment lucid, “Corona ka toh kauno pata nahi, bhookh se zaroor mar jayenge.(“Can’t say about Corona but we’ll surely die of hunger”).

The second ongoing wave that has been wreaking havoc gripped us quickly, seemingly catching us all unawares, despite similar desperate scenarios having played out in the UK, the US and Brazil. If the hyper FOMO populace had zipped through Goa & Dubai in the tiny window of respite India witnessed despite their knowledge of what the second and third waves were capable of, for rural U.P., which never reeled from the illness the way semi urban and urban India did last year, the being caught unawares aligns with the absolute lack of any attempts to generate awareness in last-mile India.

In any case, the precautions around masking up, sanitizing, and social distancing that five-year-olds have been prattling off in their virtual classrooms in Delhi and Mumbai, are rendered impractical if not ridiculous for a family of seven awaiting their turn at a pakka home under the Pradhan Mantri Aawaas Yojna, hoping to pick up work during a lockdown under MNREGA. “ Dhool mitti mein kaam kaike aawe toh nahaiye ke khaatir sabun mil jaaye bahut badi baat (After working in the dust all day, if we get soap for a bath upon return, that’s a big deal).”

“If the ASHA bahus (local term for the Accredited Social Health Activists network, frontline workers of the public rural healthcare system) would go door to door telling them about it, what to do if you’re ill, then perhaps people might get it, understand that it’s real”, says Lalita, KL’s senior producer, whose extended family back home in Jahaddipur village in Ayodhya, are all unwell and have “all the COVID symptoms” that Amitabh Bachchan tells you about as you wait for the caller tune to end. But even that booming baritone is only available to those who have smartphones after all.

Where are the ASHA workers then, whose job is precisely that – going door to door creating awareness. According to protocol, their task, alongwith the rozgar sahayaks, in the wake of recent reverse migrations and Kumbh mela was to identify potential cases, and keep tabs on them. But many of them have switched off their phones in Jahaddipur village and surrounding villages, we learnt. Perhaps they are ill themselves, they are frightened, they know only too well that medical help, real medical help, is at least 20 kms away on foot – and even that’s the best case scenario. Awareness too comes at a price then; in all likelihood, they are putting down figures into their registers/punching them into their smartphones “ghar baithe-baithe”, is Lalita’s guess.

The ultimate irony perhaps that they’re the ones following the baritone’s exhortation to stay inside our homes. Perhaps the fact that they’re the scarred warriors from last year who were inducted into keeping track of cases, particularly of those homes that had their loved ones returning, often dealing with non-cooperation at best and subjected to harassment at worst, is also a factor here. As Lakshmi Devi, an ASHA Sangini from Khiriya Latkanju in Lalitpur had shared in this Chambal Media-TTE video short, “When we go to get the details of anyone who has come from outside of the village, they get aggressive. Some abuse us and even beat us. They accuse us of lying about them being covid positive even though we tell them that this is not just for positive people. We just want to get their travel details, the place where they have come from or whether they have any symptoms. But most abuse us and refuse to give out any details.”

Fates writ in Distances & Resource Crunches: Of Inaccessible & Broken Healthcare Systems & Community Centres

“My village is in the outskirts,” Lalita shares, “To get to the nearest possible place from where you could hope for an auto (to get to that medical centre 20 kms away) is a 3-4 km walk. If you have a high fever, that’s not really a workable option. I don’t know what to tell my uncle and his family either.” People generally wait for larger numbers to consider this option in order to justify the “auto ka kiraaya (travel fare).” What’s easier, more convenient, and most importantly, cheapest, is to knock on the door of the nearest neem-hakeem medical hack (almost lovingly termed jhhola-chhap doctor), but most of them too have shut shop in the last month.

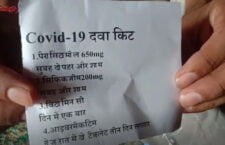

What it has boiled down to then are quick relief measures – take a pill to get the fever down, drink cough syrup for the cough and make do, move on. When things get really bad – rasping breaths – there is a sense that death is close, which is sometimes accompanied by last-minute scrambling for help. That is 20+kms away. For those who make it to these primary health centres, dying patients’ kin are more often than not met with familiar dictums, ‘Lucknow referral’, ‘Kanpur referral’ –

pregnant women have lost their unborn babies in these non-stop referral games; these have been part of the normal, both old and new. As is death. “Kya pehle log nahi marte the? (Didn’t people die earlier?)”, is the non-sequitur that Lalita found herself having to respond to each time she suggested that people get their RT-PCR tests done, a macabre echo of sorts of what the Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar had said recently about the death toll in his state.

Women dying during routine sterilization procedures, entire villages succumbing to tuberculosis, young men falling prey to medical malpractice, bodies gone missing overnight, victims of sexual violence, the mining mafia, caste prejudice, lives negotiated over samjhauta, compensated for in hard cash, cattle, maybe a motorbike, rural U.P. has seen it all, and continues to. If Lucknow and Kanpur are buckling under the stress on their systems, forced to turn away patients, cities reeling from testing delays, among other things – the sheer number of cases flowing in from rural and small town U.P. – for the existing rural healthcare systems the pressures and resource crunches are par course. It is wiser to not partake of them, is the standard belief, and not without reason. “I would never visit a government hospital if it were upto me”, a patient suffering from pneumonia had told KL – another silent killer in the hinterland, a disease that, like TB, is curable. Another “mahamari” if you please leading to sickness and perhaps death – the vocabulary addition this disease’s only real achievement as far as rural U.P. is concerned.

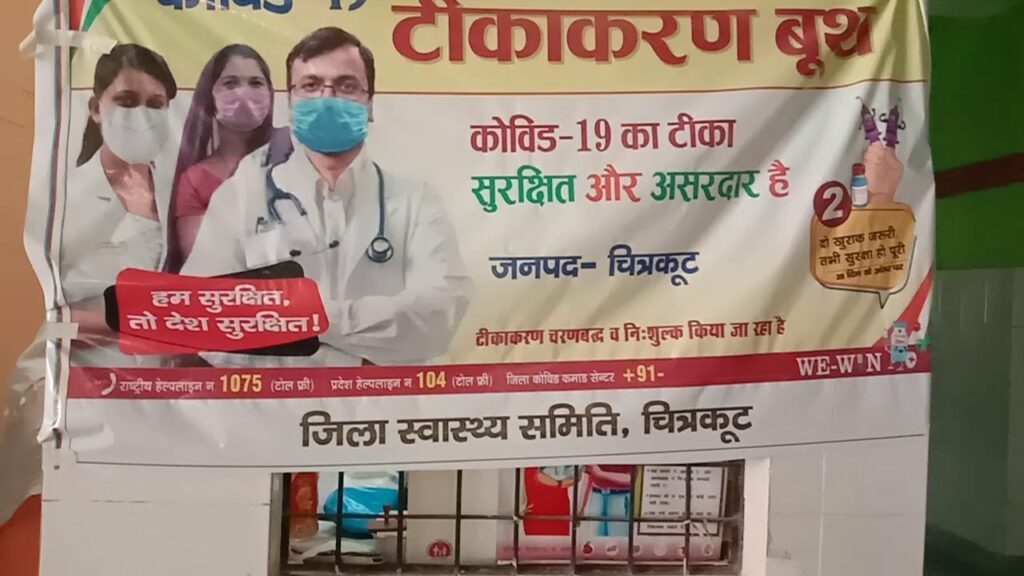

Mind the Tika Gap: The Vaccine Discrimination Nobody’s Talking About

While vaccine pricing debates continue to pendulum-swing between free-for-all and expensive-for-some, the burden to bear that is the unfolding vaccine discrimination lies with rural India. The digital divide in India, like every other divide, has risen and manifested itself in stark ways all through the pandemic. While the deeply flawed education system led to similar tragedies both in urban and rural India last year during the peak of the first wave, the gender, geography and income skews that are built into the very system affected those on the margins in much more adversely severe ways.

With teledensity at around 57 percent, according to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, for instance, the chances of high-speed internet and smartphone access were slim to none for students of rural primary schools. In the current context, this automatically cancels out any hope for rural India vis-à-vis say Twitter SOS posts and tags at 3 am that are the norm in urban scenarios. But while the imagination around last-minute life-saving posts on social media can be the stuff of dreams or visionaries, what is more pressing during the second wave is that access to the only “solution” to the crisis is via an app that requires a device, internet, electricity, and at least a basic understanding of English. A language that according to the Lok Foundation survey, is spoken by only 3% of its rural respondents. Furthermore, the need for Aadhaar documentation that has been a highly contested issue over the years ever since it was launched, specifically the biometrics aspect, and most recently in the context of the pandemic and PDS, in order to register on Cowin, renders the vaccination drive the very opposite of inclusive, no matter the packaging around tika utsavs and dawai- bhi-kadaai-bhi monologues that the Centre might be invested in.

Elections in the time of Corona: How Panchayat Polls Added to the Misery

What medical crises cannot pull off, politics can. Dinesh Kumar, a candidate slated for a win at the recently concluded panchayat polls in Uttar Pradesh, from gram panchayat Vijayanpur Sajahra sent a “chaar-pahiyaa (four wheeler)” to Jahaddipur village to ferry the elderly and the sick to the polling booth so they could cast their votes. While the hard truth – that no cars will be sent to take anybody battling between life and death in those precious moments that make all the difference – is not a hidden one, the importance of panchayat elections trumps all. Across India, panchayats implement nearly 70 percent of rural development programmes.

Most government schemes including the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, (MNREGA) are largely implemented through panchayats in villages, since they are the local governing bodies. While the Yogi government’s conveniently feigned helplessness at the Allahabad High Court ruling to hold panchayat elections in the midst of a pandemic doesn’t sit right with its previous refusal to implement a lockdown order by the High Court among other progressive Allahabad HC rulings, the reality on the ground is that janta considers them supremely important too. A matter of life and death beyond mere illnesses, as they understand it. Migrant populations returning to U.P. from the cities in the second wave timed their return with the casting of votes, since the chances of the release of funds into their accounts via the much-acclaimed DBT’s, or their names finally appearing on the housing scheme waiting list, are favourable in panchayat season.

Needless to add, any COVID 19 related protocol, including masking and social distancing were completely done away with at polling booths and elsewhere, with no protections put into place either by the administration or thew candidates themselves, even as teacher’s unions in the state alleged that 577 teachers and support staff who’d been out on panchayat poll duty, had died. “Elections are like weddings,” Lalita was told, “When the mahurat (timing) is right, it has to be done.”

This also explains the rationale behind the belief that COVID 19 either doesn’t exist or is at best, a seasonal flu (more on this later in the article). Or as a gentleman manning a polling booth in Ayodhya told KL, “Chunav ke time corona nahi hota. (There’s no Corona when elections are on).”

It’s all in the Mind: A Culture of Dismissal, Denial, Suspicion and Fear

In Manikpur interiors of Chitrakoot district, locally known as patha kshetra/pahaadi ilaaka, known for its rocky terrain and thick forests that lend notorious outlaws hiding places, home to tribals who survive on selling wood, a band of vigilantes formed almost overnight around the same time that Cowin registration opened up for those above 18 years of age. Their mission? To protect themselves. From the vaccine. “We’ll smash anyone who enters our villages with the mandate to vaccinate us all”, said a local trusted source, member of the vigilante group, to KL over a phone call. This extremist situation has risen aftern months of locals in Banda, Chitrakoot, Mahoba, and other parts of rural Bundelkhand have tired

themselves crying hoarse, “This is only seasonal. Why the hue and cry?” There’s been a response for almost every point that pandemic awareness has taught us by now, which boils down to “Hum yeh sab nahi maante (We don’t believe in all this).” What about the high fever? “We’ve seen worse with malaria and typhoid, which come every season, just before and with the monsoons. It is a lack of hygiene. Why can’t they have our villages cleaned up instead?” The cough? “We’ve seen worse with dust from the crusher machines, mazdoori, TB.” The breathlessness? “If you wear these stupid masks, what do you expect?

Besides, the cities have no open spaces to breathe, must be that.” What is Corona then?

“Humein laagat hai Modi kauno virus hawa ma udaay dehe hai. (If you ask us, it seems like Modi has created this rumour of a virus that’s now floating about).”

This is not so much fake news that could have your property seized as per the state C.M.’s directives, but an entrenched distrust and also mistrust of government-led initiatives. The admonishments have been replaced with fear seeped in a mistrust of information that flows top-down, a distrust of governance and many, many real-time episodes.

Such as the one about the “lambe chaude” Sharma brothers from Lalita’s village in Ayodhya who went to the dispensary complaining of “a light fever”, were administered “an injection” and ended up dead. The facts of the case are not certain at all, and details change depending on who you ask, but the takeaway for the village has been what Lalita’s now told each time she speaks to her family, “Do whatever you want but please don’t take that vaccine.”

The workings of belief and fear are as complex as the workings of systems should be straightforward; they are not addressed in awareness drives and caller tunes, in media and culture, at least not in ways and languages that are accessible. This is why while vigilantes against vaccines are forming overnight, nobody’s thinking twice before disposing off a used PPE kit gear in Banda, bang in the middle of a residential mohalla.

Written by Pooja Pande for Khabar Lahariya.

(An edited version of this article was published as an Article 14 exclusive.)