Naved Aslam smiles the sweetest smile you’ve seen in your life when asked about Diwali. In his blue, collared shirt, his jet black hair parted neatly to one side, he says, “Bahut maze se manaate hain (We celebrate with great enjoyment). Papa-mummy bring crackers and I celebrate with my brothers and sisters.” Diwali is five days away when we meet Naved who is full of anticipation.

“Diwali toh khushiyon ka tyohaar hai (Diwali is the festival of happiness),” he explains. And what do festivals bring if not happiness?

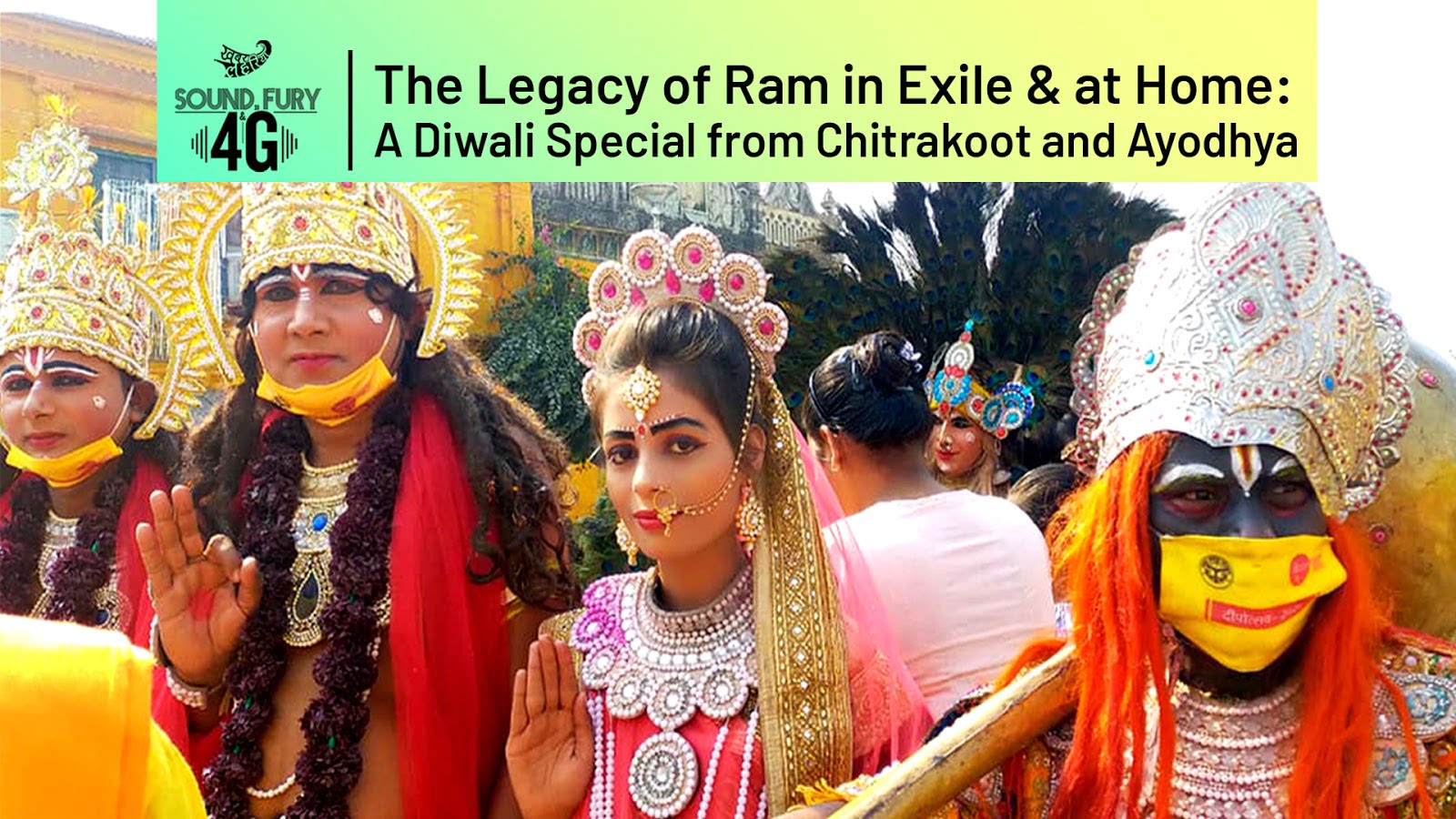

The week before Diwali in Bundelkhand, Khabar Lahariya senior reporter, Nazni Rizvi has set out to understand what it’s like to be a resident of a physical space that is saturated with the mythological memory of three former residents in exile.

Even in 2020, centuries later, everyone here knows the story of Ram, his brother Lakshman and wife Sita who called Chitrakoot home for 11 to 14 years (depending on whom you ask) during their exile from the kingdom of Ayodhya. Naved prattles off easily: “After 14 years of exile Ramji returned to Chitrakoot … when he defeated Raavan and returned, all the people of the kingdom lit lamps and celebrated. This is what we call Diwali, and this is what we all have been celebrating since then.”

While Naved’s telling might differ slightly from the more conventional party-line of Valmiki’s Ramayana, who’s to say that his version doesn’t count?

“The number of Ramayanas and the range of their influence in South and Southeast Asia over the past twenty-five hundred years or more are astonishing… Camille Bulcke, a student of the Ramayana, counted three hundred tellings,” wrote the academic A.K. Ramanujan in his essay, ‘Two Three Hundred Ramayanas’ for which he got into trouble years after his death.

Of course there are people who are deeply invested in one incontestable and authoritative telling of the Ramayana. In 2008 the student wing of the RSS, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) vandalised the history department of Delhi University and successfully demanded the essay’s removal from the university reading list and Oxford University Press’s publications.

Back then when mainstream Hindutva was largely still the boogie monster under India’s bed, you could already hear the rumblings of the Ram Rajya that was to come to fruition twelve years later, in the Ayodhya verdict of the Supreme court.

The historian Sheldon Pollock builds a case for why this uncontested Ramayana narrative is so important: “It is doubtful if any other text in South Asia has ever supplied an idiom or vocabulary for political imagination remotely comparable in longevity, frequency of deployment and effectivity,” he writes.

Pollock, who has been similarly unpopular with right wing ‘intellectuals’, suggests that it was only in the 12th century that the Ramayana came to inhabit a central public political space from a more literary space — in response to the encounter with the Ghaznavids, Khaljis and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate, although there are also more syncretic artefacts from this encounter and evidence of peaceful coexistence in the subcontinent. In 1913 R.G Bhandarkar too claimed that while the divinity of Ram was known early on, the specific “temple-cult” of Ram was slow to develop.

However, this contradicts the “sanatan dharma” ideology of the right wing that insists on historical evidence for a temple underneath the Babri Masjid, Hanuman’s bridge from India to Sri Lanka and the absolute historical truth of the Ramayana.

Why the Ramayana narrative captivates national imagination

The appeal of the Ramayana lies in its narrative that made Ram and no one else, the figure of cult and royal identity for kings of the period, writes Pollock. It proclaims two things: “first, that the order of everyday human life is regulated by the active, immanent presence of the divine; second, that those who would disturb or destroy that order must be enemies of God and not really human.”

The Ramayana is profoundly and fundamentally a text of “othering” writes Pollock — as opposed to the aporia or less straightforward Mahabharata where the Kaurava “others” are in fact “brothers”. This medieval coding of the Ramayana was reactivated in the choice of Ayodhya, the birthplace of Ram, as the site of struggle dating back to Advani-era BJP, and in the Sangh’s attempts to represent Muslims as demonic others — an orientation that has percolated into contemporary mainstream media. In 2020 it is evident who these enemies of righteousness, nonhumans or others are supposed to be.

More importantly, in Valmiki’s Ramayana, you have the god-king, Ram — the only being capable of combating evil. Even when Ram acts in a manner that seemingly goes against “goodness”, such as the murder of king Vali, the text takes this position: “It is kings-make no mistake about it-who confer righteous merit, something so hard to acquire, and precious life itself. One must never harm them, never criticize, insult, or oppose them. Kings are gods who walk the earth in the form of men.” 1

Anticaste leaders like Periyar have contested Ram’s divinity in his critique of the Ramayana as a tale of Aryan expansion into Dravidian land; others like the Dalit Ramnamami sect in Chhattisgarh have scrubbed the Ramayana of troubling casteist connotations and improvised their own telling incorporating Kabir dohas.

Still this rhetoric of kingly Hindu divinity, above critique has endured. We hear its echoes in recent slogans of 2019’s Modi hain toh mumkin hain, and the almost ubiquitous presence of U.P. Chief Minister Ajay Bisht aka Yogi Adityanath, across election campaigns in other states of the country, most recently Bihar .

In November 2020, the “Ramayana has increasingly become about Ram Rajya — a kingdom being restored,” Arshia Sattar who has written multiple books translating and retelling the Ramayana told The Wire. In keeping with that special brand of ghar wapsi the UP CM dabbles in, she is often told, ‘Oh very nice, more Muslims should be like you’.

Chitrakoot: a symbol of inter-religious harmony?

In Bundelkhand’s Chitrakoot the legacy of the Ramayana is everyday, inescapable, and decidedly local. From Ram Ghat where the family was said to bathe, which is a major site of pilgrimage dotted with temples, to Dharam Nagari (city of faith) Rajapur where Tulsidas is said to have written the Ramcharitmanas, which is replete with crumbling havelis and a decrepit Tulsidas Memorial — the land is rife with mythological significance, its monuments markedly subject to the passage of time.

But Chitrakoot is also very specific in its history of “kaumi ekta” (communal harmony) in comparison with the more bloodsoaked history of Ayodhya. In fact there are old imambaras here under the stewardship of Hindu families. The Rama ka Imambara is famous as a shining symbol of the “Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb”. It was built in 1750 by Ramaji Rao, a Marathi soldier in memory of Imam Hussain, and till date is an important site for the Muharram procession in Banda, its duties carried on by the descendents of the Rao family.

In October last year, Nazni reported on Chitrakoot’s past and present of communal harmony. “Whether it’s a Muslim festival that’s celebrated by Hindus or vice-versa, people of all religious communities not only partake but also jointly organize the celebrations,” said Shabeena of the Vanangna Sanstha in Banda. Plus the local administration is “tight” with no tolerance for religious troublemaking, she said.

Narendra Gupta, chairman of the Municipality of Karwi, Chitrakoot told KL, “The Ravan effigy burning tradition is celebrated both by Muslims and Hindus. During Muharram, the soil for the Taziya (replica of a tomb, carried during processions) is first taken from Hindu households. Another great tradition is that of eating paan together as a festive tradition during Dussehra.”

Such a strong culture of goodwill is remarkable in light of data, which states that Uttar Pradesh has reported the most number of incidents of communal violence over the past decade. In Chitrakoot, Muslims are just 3.48% of the population, compared to the majority Hindu community whose share is more than 96% per the 2011 Census.

As Diwali, the time of Ram’s symbolic victory, drew closer this year we wanted to unpack this fabled communal harmony.

After all the clarion call of Ram Rajya and sanatan dharma has turned Ayodhya into commemorative ground, symbolically housing gods while overlooking its ordinary people. In August 2020, KL reported on the villagers of Manjha Barheta, near Ayodhya, who are opposing the building of a 200 meter high statue of Ram which would displace them from their homes. As 6 lakh diyas light up the dream of a “Navya Ayodhya” per the grand plans of the UP government, residents of Jamthara Ghat beside Ayodhya rue their dismal Diwali in the shadow of Covid. They told KL of daily-wage labour which fills their bellies only in the evening, the army settlement shooing them off from trying to use the closest toilets and living in shanties. “Our people have been here for 200 years. When will the light reach us?”

So as Diwali approached, we wondered: has Chitrakoot stayed peaceful because such dispossession has not yet touched close to home? Its people do not live on literally contested ground. Or is it a different idea of Ram that prevails here than the victorious warrior-Ram of Ayodhya, he in whose name the kar-sevaks would bring down a mosque and murder the demonised Muslim “other”?

Is it a more peaceable, gentler Ram, estranged and grieving the loss of home and family, living closely entwined with nature, that gives Chitrakoot its unique character? One year after her report, Nazni set out once again, asking this time what idea of Ram lives in Chitrakoot’s contemporary residents, how this communal harmony permeates their lives and whether they felt that governance in recent years has changed things.

“Rom-rom mein Ram, kan-kan mein Ram Raghuram (In every hair, in every particle lives Ram Raghuram)” smiles a gentle mustachioed Ram Niranjan Singh in Deokali village, 12 km from Chitrakoot.

Mild-mannered and polite through the conversation, he tells Nazni, “We aspire here to meet the idea of maryada purushottam that Ram was — an ideal respectful society we model on him.” On Holi the Muslims play with us, Deepavali, Dussehra—they take part in our festivals and vice versa, he says. “We Hindus don’t make the Muslim sewaiya at home but we eat it,” he says.

Politics percolates in. The government is doing alright, in his opinion — perhaps giving a little extra attention to religious affairs. Recently he recalls, the village of Lalapur beside Deokali had some conflict because they were demanding acknowledgement that Valmiki who wrote the Ramayana was from there. “But Yogiji went there, he climbed up the 300 steps and established the truth, that yes, this is where the Ramayana was written.”

This is how truth is established in Chitrakoot. Local belief and a little bit of state-sponsored validation.

On the banks of the Ram Ghat, pujari Vijay Shankar Tripathi tells KL reporter Sahodra about the Balaji mandir, purportedly constructed by the Mughal king, Aurangzeb. “Aurangzeb was the kind of ruler who, if he experienced some kind of feeling himself from the sacred Hindu sites then he would do something good — else he would break the murtis. When he came to the Shankar temple here, that’s exactly what he did, and then he and the whole of his army got afflicted by kala azar (plague),” he says. According to Tripathi Aurangzeb repented and all was well.

When asked about where he has learned about this history, the pujaris there say “yahaan ke logo ka kehna hai (That’s what people say here).”

Back in Deokali village, gentle Ram Niranjan Singh grows stern, says firmly, “Look the people who are reasonable, they know, la ilahi ilallah muhammad rasoolilah – ishwar ek hain iske naam anek hain (God is one, we call him by different names). Both Hinduism and Islam are flourishing religions, we coexist. The rest who don’t have sense, they make trouble, assert that I am Hindu, I am Muslim, I am Sikh… ”

Taqseem Saudagar whose shop is stacked with Diwali lights and firecrackers, adds to this happy image of secularism. “In the run-up to Diwali we buy things on Dhanteras — fridge, dishes, a car,” he says. “Muslims get equal respect to Hindus here; we eat together, sit together, attend each others’ weddings.”

As someone who grew up here, Nazni too feels that the cultural aspects of Hindu festivals have fully permeated into Muslim households. Her conversations with other local Muslims buttress this claim.

Aslam Husain Khan, a school-teacher in Throwa recalls, “Since I was a child, when Diwali would come around, mujhme ek ajeeb si umang aur ullas paida ho jaati thi (I would be filled with a strange exaltation and glee). I would coax my mother to get pataka, phuljhari, throw tantrums for the little Diwali toys from the markets. We would light diyas at home, and also make the Holi associated food .”

Aslam Husain Khan pf Throwa says, “Since I was a child, when Diwali would come around, mujhme ek ajeeb si umang aur ullas paida ho jaati thi.”

“I have also seen this in my other Muslim brothers — even if they don’t go to the extent of preparing the food, they enjoy the Diwali crackers, the colours on Holi… I’ve heard stories of Ram while growing up, I graduated from here and during college we often used to go to Chitrakoot for pilgrimage. I’ve spent my life with my Hindu friends and of course that has had an influence on me.”

But have Muslim festivals entered into Hindu households as fully, Nazni asks. The somewhat inadequate chorus that greets her is “sewaiya” — much in demand by the local Hindus during Eid, but not prepared at their own homes. Young Naved Aslam’s classmates ask him to bring sewaiya from home during Eid; teacher Aslam Husain Khan’s female co-teachers have asked him to share the sewaiya recipe.

Nafeesa Begum and Rasheeda Begum speak of gale milna, phone calls with good wishes, home-visits, treating close friends to sewaiya on Eid and giving children Eidi. Rasheeda Begum has personally taken her guests for picnics to Chitrakoot, been to the Chaaro-dham and believes that there is knowledge to be gained from here as well.

“It is through the festivals that we express here ki Hindu-Muslim ek hain. (Hindu-Muslims are one.) Baaki logo ke mann mein kya hain, woh toh hum nahi bata sakte (Outside of this, I can’t say what is in the minds of people),” says Rasheeda Begum.

“While the Hindus here don’t make the gosht (meat) or sewai we do, they do come eat at our homes on Bakr-Eid,” says Yasmin Sagar. “Baaki itna interest nahi le paate (Other than this they don’t take much interest).”

While she knows a lot about Ram from living in Dharam Nagri, where Hindus are more in number, she feels “Hindu log jo hain, woh musalman ke dharam ko kam maante hain (The Hindus here think less of the Muslim’s religion).

Shankar Gupta of Karvi claims that in Chitrakoot, during Moharram, 70% of Hindu brothers help with the preparations, help with transporting the tajiya. “There has never been any communal violence in Chitrakoot,” he says, “other than “chhut-putt” incidents he doesn’t elaborate on. Perhaps the lakshman rekha that halts the sewaiya at the doorstep of most Hindus is a sign.

In Banda, Chitrakoot in keeping with the narrative of interreligious cordiality and participation in each others festivals, Hindu households string fairy-lights down their houses during the Muslim occassion of Barawafat. For the first time this year, none of the houses around a local temple put out this jhaalar. The street stayed dark.

Gentle-mild mannered Ram Niranjan Singh of Karvi’s Deokali village where there are no Muslims at all says that there has never been any communal violence here. He looks Nazni straight in the eyes and says, “Hindu jaldi dange phasaad mein nahi padhte. Aur dange ye log zyada karte hain — Muslim log. (Hindus don’t get involved in much rioting or fuss. That these people do more of — the Muslims). Because there are no Muslims here, there is not much chance of violence.”

The Ayodhya verdict creases an ecstatic smile across his face. “Humaare itihaas rach diya Ayodhya. (It was historic.) It had been dragging for so many years, they resolved the issue somehow. Because Hindu Hindu-staan hain, jo Hindu ka isht hai, usi murti ko hona hi chahiye. Agar aisa nahi hai, toh kaahe ka Hindustan?”

(You see, Hindustan is the place of the Hindus. That which is sacred to the Hindus is the statue that should be there. If it is not so, then what Hindustan?”)

From Nazni’s conversations with both Hindus and Muslims in Hindu-majority Chitrakoot, the layers start to unfurl revealing a familiar bigotry, perhaps more benign at the moment. As long as the Muslim minority assimilates, all is well. But scratch the surface and you get the sense that something dangerous lurks here.

Nazni recalls how after the lockdown, the meat-shops stayed locked long after all the other shops in the market were allowed to reopen. Those who returned from the Tablighi Jamaat gathering (or even believed to have returned, based entirely on their names) were harassed persistently and disproportionately by the police who sealed off and kept patrolling the Muslim neighbourhoods. KL Editor in Chief Kavita Bundelkhandi responded to a distress-call from Gularnaka in Banda where an Tablighi Jamaat attendee and his family had been taken into custody by the police. Following that, the entire area had been sealed off to the extent that they had no access to vegetables or basic medicine. “If we even stand at the door, the police turn up immediately. Humare ghar mein namak tak nahi hain, doodh nahi hain (We don’t even have salt or milk in our homes), the woman said.

When Nazni asks Rasheeda Begum about life after Yogi, Rasheeda looks around the room, and hesitates. “Arre…” she says, trailing off.

Rasheeda Begum insists there is misunderstanding among Muslims who feel unsafe but trails off when asked the impact of CM Adityanath’s policies

Yes there has been kaafi badlaav (a significant change), she feels. “Muslims have started thinking that humaare saath galat ho raha hain, hum surakshit nahi hain (we are being treated wrongly, we are not safe). But if Yogi is giving something like houses or some facility, everyone is getting it right?”

“Yes there are some people who do wrong things and because of that the sarkaar gets a bad reputation,” she says trailing off again. “Ghalat fehmi baitha hain (It’s a misunderstanding among Muslims),” she says. When pressed on the excesses of the police during Covid she has this to say: “They must have felt there is more khatra (danger) from the Muslims.”

Of sacred places and ruin: Dharam Nagri and the pujaris at Ram Ghat

Ram Ghat in Chitrakoot, on the banks of the Mandakini river, is a major tourist attraction. You can even find it on Trip Advisor with a 4.5 rating from 67 reviews. Amit Kumar from Kanpur recommends the boat rides for the entire family for Rs 150. Boats come replete with “LED lights, rabbits and a music system” and “play bhajans to make the ride soothing” as they make stops at the various temples, he writes in his review.

It is believed that Ram appeared to Tulsidas here as he was scrubbing for chandan, back when Chitrakoot was just forestland. If you stay six months here meditating and chanting Ram’s name, you too will be blessed with a vision, the pujaris are quick to assure you. “There is no guarantee at the other religious sites, but in Chitrakoot, you’re guaranteed a visitation in 6 months.”

Pujari, Vijay Shankar Tripathi guarantees a visitation from Ram in 6 months at Chitrakoot, if you perform the tapasya conscientiously

“Chitrakoot Bharat ka hriday hain (Chitrakoot is the heart of Bharat), it pulls every pilgrim towards itself with a gravitational pull,” says Vijay Shankar Tripathi, a pujari at the Tulsidas mandir inside the Damodar Das cave, some 8 km from Ram Ghat.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pujaris at Ram Ghat are as unanimous in the primacy of Hinduism as the sanatan dharma (eternal religion), as they are to consolidate the mythology of Chitrakoot as a place of religious confluence and peace.

Ramkishor Baba cites Tulsidas and Rahim’s time together at Chitrakoot, waving away any notion of religious animosity. Rahim was a Muslim saint after all, he says.

“No religion teaches you to commit violence or force your religion on someone else,” says pujari Vijay Shankar Tripathi. What about the spike in violence against Muslims in the country in recent years, the Delhi pogrom in February? “Hindu ko hawa lag jaati hai toh woh karenge (If the wind [of provocation] touches the Hindus, then they too will be violent),” Tripathi says casually.

On the matter of the central government, and Uttar Pradesh government’s focus on religion Tripathi feels that governance and “dharam” are two sides of the same coin, but there should not be an excessive overlap between the two. Tripathi has his own list of wants that remain unfulfilled even by this government modelled on Ram Rajya: a fund for pujaris who have been impacted by the Coronavirus, for the government to investigate people who do “social corruption”, and to turn its attention towards the many temples that are left empty or crumbling with pujaris whose fate seems to depend on the stars.

“Look, for the government mandir and masjid are the same thing. Now the mandirs that are old, are falling, are breaking— the government should take care of them, get them inspected and repaired properly,” says Tripathi.

He gestures around the mandir, the paint peeling above his head. “Itni puraani imaratein kahaan ab banai — par Yogi ho ya mahant — iske upar kisi ka nigaah nahi hain. (Such old buildings — where are they made now? But whether Yogi or monk — no one’s attention is on them.)”

“Whereas we read in the papers, watched on TV that old mandir-masjid ka jeevan uddhar karaya jayega — their lives will be salvaged. These ancient mandirs are right there in front of the ghaat. They should research and find out — if they come here we would tell them, but they don’t come to see.”

“What is the point of talking about these news mandirs again and again when there is no capacity to even look after the old ones?”

To understand what it means to be the tangible physical space to a mythologically significant place one could also follow the Yamuna river down to a small riverine town known locally as Dharam Nagari (city of faith). This is where locals believe Tulsidas was born, and where he wrote the Ramcharitmanas in the local Awadhi language.

KL’s report from April 2019 found that the Tulsidas Memorial here with its old havelis, and a small Ram temple in various states of decay. Rakesh Kumar, the head of the voluntary Tulsidas Seva Samiti was dreaming of Rajapur becoming the “Tulsidas Ramayan Hub” of the country.

These weren’t entirely castles in the air since places like the Lakshman Pahadi in Chitrakoot had been recently renovated with a new cable car ropeway, as part of the Swadesh Darshan Yojana launched in 2015. Under the Yogi Adityanath government in UP, religious tourism has received greater impetus (with the Kumbh mela budget of over 4200 crores and the renaming of cities with Farsi names — for instance transforming Faizabad as KL has always known it and called it to Ayodhya).

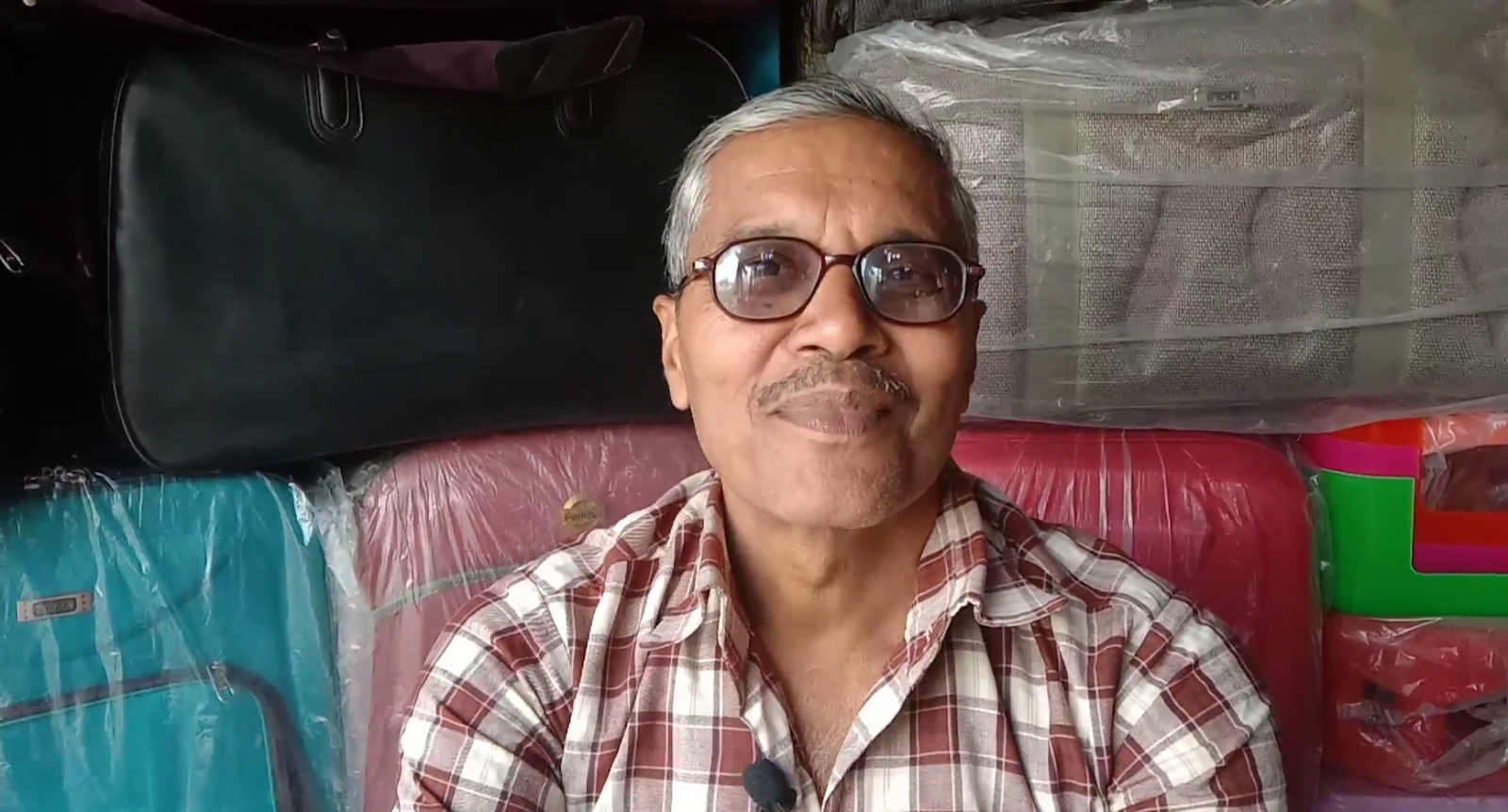

This week a year and a half later, Rajapur local Daya Shankar Dwivedi of Chilli Rakas, told KL that despite being a site of world heritage, and much talk by the government of the Ramayana tourism circuit, no Yogi budget or scheme has reached them.

“Paryatan mein aate hain aur thoo-thoo karke chale jaate hain.” (The tourists come to visit, scoff at how the place is falling apart, and leave.)

Does he think that vikas (development, the BJP mantra) will reach Rajapur?

“Ab hamein toh nahi lagta hain kyunki bachpan se dekhte aa rahe hain aur budhaape ke dehleej pe hain.”

(Well I don’t think so, because I’ve been seeing this same state of affairs since I was a child and I’m at the threshold of old age now.)

Whose Ram do you speak of?

Bundelkhand is also home to several sections of people who depart completely from this tradition of Ram worship and consider other forms of service as a form of faith in action. The Sant Nirankari Mission is one, whose members have opened schools around the country and oppose having pandits and pujaris. Another section are Dalit and OBC people who worship the constitution, or have converted to Buddhism.

In Ayodhya, Poonam Baudh, a social worker who works on women’s education, has been a Buddhist since childhood, under the influence of her Burma-born mother. This keeps her away from illogic and superstition she says. “I follow the vichar of Babasaheb,” she tells KL Chief of Bureau Meera. People believe in different kinds of Ram and if you go looking in Ayodhya, you will not find any written evidence of Dasaratha’s Ram, she says. Instead you will find Ram temples of every caste. She recites a list of examples: “Maurya panchayati sri ram jan ki mandir, kewat ram jan ki mandir, kori ram jan ki mandir, sahu panchayati ram jan ki mandir, khatik panchayati ram jan ki mandir, dhobi ka, nai ka…”

“I am Buddhist, so for me I think of Purva Ram, Sangha Ram of the Buddhists for whom there is not one single Ram). It’s about our own faith. And that does not require excavation and digging against a Quran. But there are so many – Ayodhya ke Ram, Tulsi ke Ram, Kabir ke Ram, Surdas ke Ram, Mirabai ke Ram, Valmiki ke Ram, Dashrath ke Ram, Buddhist ke Ram— Purvaram, Sangharam…?”

As far as the Ramayana is concerned she is not a fan, as a woman. “If I am pregnant and my husband leaves me in a forest, will that be good or bad?”

Poonam celebrates Buddha Baisakh Purnima she says, which marks the enlightenment of Buddha from Prince Siddharth. The occasion that holds the most importance for her however is 14th April, Dr. B.R Ambedkar’s birthday.

“It is the most important day for us. He has given us rights in the form of the Constitution which us Shudras, untouchable Buddhists use to claim and live with self respect. The day I feel the most relaxed and happy is 14th April,” she says.

There is also the 3rd of January, when she helps organise a programme to celebrate Savitribari Phule’s birthday who enabled women of all castes in India to be educated and live with equality.

To Poonam Baudh from Ayodhya the principles of Babasaheb Ambedkar are more important than any religious figure

Meera, who follows an alternative faith herself, and doesn’t consider herself religious, confesses a fondness for Diwali. She is reluctant to give up occasions to set aside work and relax, to sit awhile with the people she loves. “When else in this life of bhaaga-dauri (hectic schedules) is there time?,” she asks.

This year the usual numbers of pilgrims and tourists at Ram Ghat have dipped with the Coronavirus pandemic, and restrictions of the local government, Ramkishor Baba says. As Diwali approaches, he says, numbers will depend on what the administration will allow. He adds with an all-knowing grin: “The government can try, but on Deepavali, no one can stop the pilgrims from visiting Chitrakoot.

Call it the gravitational pull pujari Tripathi alluded to or the will of a Hindu majority, Ramkishor Baba is likely right. It’s worth mentioning, that Rama ka Imambara stayed desolate and shut this Muharram, breaking a 270 year old tradition, on strict government orders.

Perhaps it is wishful thinking but teacher Aslam Hussain Khan requests us to pass on a message to the KL audience, borrowed perhaps from his classroom full of students too, as young and hopeful as little Naved Aslam. “Diwali mein hai Ali aur Ramzaan mein hai Ram aur dono dhrashti mil kar mere desh ko banate hain mahaan.

(Diwali has within it ‘Ali’ and Ramzaan has ‘Ram’ — and both visions together make my country great).

While the interpretation, pushback and reinvention of Ram and the many faced “others” in Bundelkhand is an ongoing affair, we’re stuck on something Poonam Baudh said to us. When Meera asks Poonam what the idea of ‘Ram’ means to her, she counters with a question: “Which Ram do you speak of?

–

- Goldman, R. (Ed.). (1991). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume III: Aranyakāṇḍa. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1bmzkf0

Riddhi Dastidar is a writer and researcher in New Delhi. Their work focuses on disability justice, gender and culture. You can follow their work at gaachburi on social media.