Exodus in a Lalitpur village marks a crucial failure of the state system

In the small village of Khitwas in block Birdha, Lalitpur district, Uttar Pradesh, nearly half of its 5,000-strong population has left. With empty roads, locked homes and an eerie silence, it resembles an absolute ghost town. “These families need to leave because there is no proper work for labourers here,” said Hariprasad, one of the few remaining villagers, “They needed to leave so that they can earn money to raise their children.”

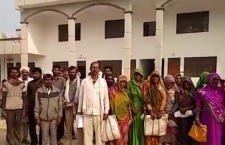

Migration for employment has reached crisis proportions in the country today, even as it continues to be a silent socio-economic phenomenon – that is, it isn’t given enough attention. 3.5 million adults in India are amidst migration plans, while 1.3 million are actively prepping for it. Employment remains the central motivation – the 2011 Census data depicts that 3 out of the 14 crore male migrants left their last place of residence in search of work. The crisis of migration is particularly amplified in Uttar Pradesh, where 26.9 lakh more people migrated out than migrated into it, the highest in any state in the country. And it is a problem that has been growing with time—between 2001 and 2011, more than 58 lakh 20 to 29 year-olds left the state in search of jobs.In our consistent reporting on migration, the crisis in Bundelkhand has been building up over decades, and the worst affected populace remain the landless, the Dalits and Adivasis. Hariprasad’s personal estimates – that 200 adivasi families have left Khitwas – confirm this too. Kanai, another villager, said, “Of 100 people, at least 50 must just be roaming around from here to there, with no land or home. But there is just no work here—what do we do?”

The solution to exactly this, proposed by then government NDA more than a decade ago, took the shape and form of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), which promises any adult who applies for employment in rural India employment within 15 days. As per the guidelines, if they aren’t given any work, an unemployment allowance has to be paid. 10 years later, even though the MGNREA guarantees at least 100 days of unskilled labour employment, the national average days of employment per household is a measly 39.26 days.

U.P.’s average fares poorly even here, with a low workday of 33.81 days. Birdha, in comparison, is slightly better at an average at 42.86 days,but this is hardly cause for celebration—it amounts to only little more than a month’s work in a whole year. The wage rates aren’t any better either: U.P.’s agreed upon rate is Rs. 175, lower than their newly revised minimum wage of Rs. 190 a day for unskilled labour. Even more shocking is the fact that between 2016 and 2018, wages were increased by Rs. 1.1 rupees even as the average inflation rate increased by more than 2%.

The lack of work is across private and public spaces, and is gradually pushing people out to nearby towns and bigger cities in search for regular livelihoods. In Khitwas, Hariprasad was like the storyteller left behind for scribes like KL reporter Rajkumari. “We left with our children to go to Indore for work for eight months,” he said, “Many go to Gwalior, Jhansi, Agra looking for work. We can’t afford to sit around and hope to find work here for eight, twelve months, can we?”

At the local employment office, Vanshilal, Birdha’s employment officer, had a confident counter argument, along the lines of,“Only those who don’t want to work leave.” He continued, “It is not as if we don’t pay well in our village. If you do the work, there is money matched competitively with what everyone else pays.All the labourers’ wages have been paid in full, and are in their bank accounts”. Vanshilal’s smugness has good reason – official data agrees with him. According to the NREGA website, 99.75% of payments in Birdha block were generated within 15 days – meaning Rs. 8.20 crores have already been paid amongst 16,488 actively employed card-holders in Birdha this year.

The daily wage labourers disagreed. Makhan, a migrant worker who was in Khitwa only as a rest-stop before she and her family headed out to try their luck in Gumma said, “The difference between working here and working outside is that there they pay us for our work immediately. Here, you don’t get paid for months on end. You need to chase them after two, three, four months after the work is completed just to get your money, and even then it’s a struggle.”

And therein hangs a tale. Vanshilal faltered briefly at exactly this point, “The labourers who are working right now haven’t been paid because the government hasn’t given us the money yet.” He continued with the PR line soon after, “I’ve asked the DM about the same; he’s reassured me that as soon as they get the money—which they will—they will pay the labourers.”

The meandering journeys of direct cash transfers into beneficiaries’ bank accounts are unfortunately all too common. Although the guidelines state that the payment has to be made within 15 days of completion and that any delays in payment entitle the recipients to compensation, stories of labourers struggling to get their due even three years after completing their tasks was a familiar tragedy in Khitwas.

The Sub-Divisional Magistrate however denied the existence of a problem, “No such situation has ever arisen,” said Dheeraj Pratap Sinha in a soft, undisturbed voice. He then passed the buck subtly, “But if it ever does, I would implore news channels like yours, to inform us of the problem and tell the people to get their job cards made so that the next time there is an employment opportunity, we can inform them.”

Until then, the 752 registered workers in Khitwas must wait for work and for due money as they watch their neighbours board up shop and leave, looking for greener pastures. All that is left for them if they choose to stay are empty promises and an empty village.

This Khabar Lahariya article first appeared on Firstpost.