Chitrakoot (UP)/ Kota (Rajasthan)/ Mumbai: Slight and dark, Shyampati, 30, leaned against a house made fragile from unseasonal rain, and talked animatedly about life as a farmer, labourer, goat-herder, mother of four, main wage-earner and full-time housewife.

Here in her rain-washed, poor village in western Uttar Pradesh’s Chitrakoot district–and across the northern plains and southern plateau–Shyampati (she uses only one name) represents a hidden Indian demographic: the Indian women farmer, almost never publicly acknowledged, reviled by superstition and patriarchy, and increasingly troubled.

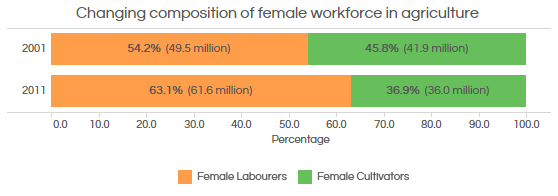

Reflecting growing distress in Indian agriculture, millions of women have gone from being land owners and cultivators to becoming labourers over a decade, according to census data analysed by IndiaSpend.

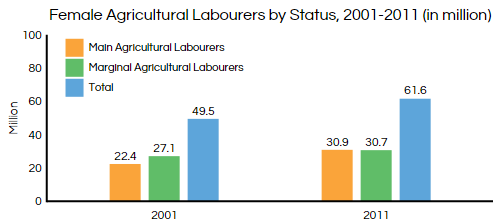

There has been a 24% increase in the number of female agricultural labourers, from 49.5 million in 2001 to 61.6 million in 2011.

Nearly 98 million Indian women have agricultural jobs, but around 63% of them, or 61.6 million women, are agricultural labourers, dependent on the farms of others, according to 2011 Census data.

Shyampati, 30, an itinerant farmer, labourer, goat-herder, mother of four and housewife, cleans grain at her home in Uttar Pradesh’s Chitrakoot district. Her unemployed husband does not help with any chores.

“We don’t own land, but I work on contract on anything between a small, half-bigha (0.2 acres) piece of land, to as much as 4 bighas (1.6 acres),” said Shyampati, who uses only one name. “Most of the agricultural seasons I get work as farm labour, and from this I earn enough anaaj and tel (wheat and mustard oil) for a year’s consumption.”

Shyampati has a daughter–who walks 5 km to the nearest middle school–three sons and an unemployed husband, who finds sporadic construction work in the district headquarters of Karwi.

“Even when he has no work, like right now, he’s not too concerned about what I’m doing, neither does he volunteer to do farm labour, which is available more readily,” said Shyampati, without rancour.

When she gets home from work, Shyampati grazes the family’s buffalo and four goats for an hour, cuts fodder and brings it home. Before and after these tasks, she cooks for the family. Her daughter helps with the utensils and clothes.

Shyampati’s profession varies, depending on the work she gets, and life for India’s rural multitaskers only gets more difficult.

The farmers India never hears about

In visuals of Indian villages, in stories about rural India, in news clips about farmer suicides or about farmers coming together to demand their rights, women seldom feature.

But women, as Khabar Lahariya reporters frequently find, plough fields, sow seeds and harvest crops–and run their households with little or no help from men, although women own only small quantities of farm land, according to a report by the National Commission of Women.

Yet, in discussions of agriculture and farming, women rarely count.

There’s an age-old–and obviously male–belief in north India that if women plough the field, there will be a drought in the village. Another belief held in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar is that if a drought does occur then women should help plough the fields–at night and in the nude.

Female farmers are particularly vulnerable, then, to agricultural decline. There has been an increase of 38% and 13% from 2001, respectively, in women as main and marginal agricultural labourers from being cultivators.

Agricultural labourers do not own farm land themselves but earn wages by working on another person’s land. Marginal agricultural labourers–Shyampati is officially one–work on farms for less than six months a year and for them farming is a secondary source of income. Main agricultural labourers farm land for more than six months a year, and for them farming is a profession and the main source of income.

The growing uncertainty in the agricultural sector has made it difficult for them to hold onto their land, which could explain the shift from farmers to labourers.

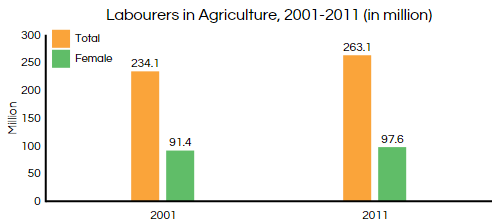

The total number of people involved in agriculture has increased 12% from 234.1 million in2001 to 263.1 million in 2011, according to 2011 Census data, while agriculture’s share in India’s gross domestic product has declined from 22% to 14% over the same period.

The number of women with agricultural jobs has come down from 39% to 37%.

This can also be attributed to the fact that the overall population of women increased 18% from 2001 (496.5 million) to 2011 (587.4 million), according to census data.

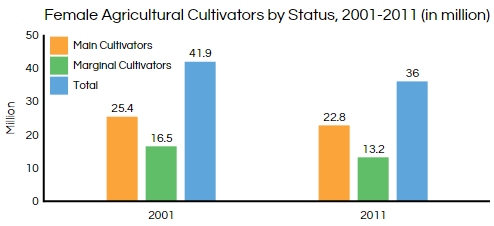

The census has divided the agricultural work force on the basis of cultivators and labourers.Cultivators, or farmers, either own or have taken agricultural land on lease/rent/contract and are involved in supervising and directing the cultivation process. (This does not include those who lease out their land.)

Against the odds, the women persevere

The total number of female farmers has declined 14% from 2001 (41.9 million) to 2011 (36 million). This includes a 10% decline in the number of main cultivators.

There has also been a 20% decline in the number of marginal female cultivators.

Although, as we mentioned, few women have land that is in their names, millions work on land that belongs to their husbands or to other land owners who contract their services as labourers in the fields.

A few fought their way to success.

In Rajasthan’s Kota district, Rippi and Karamvir (both use one name) are well-known faces in their village, often riding high on tractors across their 80 bighas (32 acres) of land.

In Rajasthan’s Kota district, Rippi and Karamvir (both use one name) are well-known faces in their village, often riding high on tractors across their 80 bighas (32 acres) of land.

When the crop is ready, the two sisters harvest and carry it to the mandi (market).

“We started working the fields when our father passed away. We had all this land but no one to work on it,” says 30-year old Rippi.

Karamvir, 24, said villagers did not take kindly to their first trip on a tractor.

“All hell broke loose,” she said. “We refused to give in, and gradually people also came around to the idea of two young women working the fields.”

At the mandis, they often faced obstacles; drunken men are still a common problem.

“Eventually we had to take help from the district administration and the local police,” said Rippi. “We haven’t looked back since.”

(This story has been produced in partnership with IndiaSpend, the country’s first data journalism initiative. IndiaSpend utilizes open data to analyze a range of issues with the broader objective of fostering better governance, transparency and accountability in the Indian government. Abheet Singh Sethi is a policy analyst with IndiaSpend and helped put this story together.)

Click here to read story on IndiaSpend