Towards the end of World Suicide Prevention Month, we document how the youth of Bundelkhand (and beyond) are collapsing under the weight of their crushed dreams while a callous system of selective outrage plays out on national television. Read our special ground report from rural UP.

Turn your television on or swipe through your twitter feed, and chances are that you’ll find yourself swept away by the deluge that is the media coverage of Sushant Singh Rajput’s suicide. The young actor took his life in June due to severe and chronic depression. However, instead of attempting to combat the mental health crisis exacerbated by the pandemic, the might of our media and government apparatuses seems to be focused on propagating conspiracy theories, each one more absurd than the next.

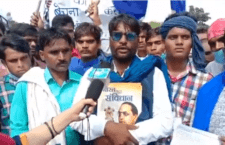

Mainstream media outlets rapaciously mounted a witch hunt culminating in the arrests of members of Rajput’s inner circle instead of recognizing that the mental health crisis in India is real; after all, it’s easier to blame a woman for being a seductress or a witch than to acknowledge that since the beginning of the lockdown, the number of mental illness cases in India has increased by 20% and that at least one in five Indians has been affected. Predictably, the media’s obsession with the sordid details of Rajput’s personal life means that their coverage of the myriad other suicides in the country has slowed to a trickle. This September, during the World Suicide Prevention Month, we shine a light on the untold stories of suicide, crumbling healthcare infrastructure, and other quotidian crises from India’s hinterlands that are being sidelined in favor of easy and sensational media fodder.

In Banda, we met the family of 24-year old Sant Kumar, a bright student from the Tindvari block in Paparenda village, who committed suicide due to financial pressures that thwarted his dreams of becoming a Ph.D. candidate. On August 27th, Kumar hanged himself from a tree about a kilometer away from his house.

Ram Aashre, the SO of Chilla Thana said that Sant Kumar was frustrated with the financial situation of his family, leading him to commit suicide. As per sources, Sant Kumar was a B.Sc. student who wanted to do a Ph.D., for which he needed 2.5 lakh. He shared these plans with his family members but is limited by financial constraints they told him to stop studying. Discouraged, Sant Kumar hanged himself. As of now, an application has been written and his body has been sent for an autopsy.

Kalavati, Sant Kumar’s aunt, lamented, “He needed money to study. But, we are laborers. We had 4 children to feed and have to get our daughter married off too. Now, should we pay for her wedding or his studies? He wasn’t physically fit, so he couldn’t help us out at the farm either. He wanted to study more, but where were we supposed to get the money from? So, he left us. He got angry, and left the house, and then hanged himself. His mother, father, and even sister realized he left in anger, but nobody in the family thought he’d do something like this. We all thought he was just angry and wanted some air.”

Shivadhar, Sant Kumar’s uncle seemed perplexed at the state of affairs, “He had finished his BSc…He wanted to do a Ph.D. and needed 2.5 lakhs. We told him that we will give it to him, after working and taking loans, but we couldn’t right now. After finishing off his studies, he’d go to our farm as a lookout. In the evening, he left as usual…I got the news [of his suicide] in the morning.

Sant Kumar’s brother Guru Prasad tells us about the plans for a shining, exciting future his brother and he had made together: “Personally, I can’t see a valid reason for suicide. After he finished his BSc, he told me he wanted to do his MSc. I told him to go ahead and do it. He was preparing for his fourth semester when the lockdown happened. After that, he would have started preparing for his Ph.D. He would study all day and then until midnight as well. Once, a couple of days ago, he said he wanted a motorcycle. I told him to first focus on his studies, and then I’ll buy him a motorcycle. I told him, ‘once the harvest is ready, I’ll buy you a motorcycle. For now, focus on your studies.’ He said he wanted to do a Ph.D., so I said, go ahead. We told him we’ll adjust and figure out a way to arrange the fees.”

Yet, Sant Kumar’s suicide demonstrates the hollowness of his brother’s promises. Generational poverty exacerbated by excessive borrowing guaranteed that Sant Kumar’s dreams would be rendered incomplete. While Sant Kumar’s death highlights the disparity between the dreams of the rich and the poor, 19-year-old Vandana’s suicide in Mahoba points to the deleterious effects of the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown on the aspirations of India’s poor.

Vandana, a young woman from Kotwali in Mahoba ingested poison after being unable to give her B.Com exam, which was canceled due to the pandemic. In spite of being rushed to the hospital, she succumbed to her condition. “She had 3 papers left to give. They said that the exams would be in July, but that didn’t happen. So she felt that the year had gone to waste. She said, ‘you had worked so hard and paid for my education. Now, it has all gone to waste.’ says Baburam, her distraught father, who couldn’t fathom his loss.

“She never got into fights with anyone, would always mind her own business…She was my youngest daughter… I am a farmer. I don’t know what to say, beta. I’m nothing without my daughters. If you ask for my blood, I’ll give it all to you! I’m an illiterate man, I can’t sign my own name. All she wanted to do was study. She used to score extremely high as well. She would have been done with B.Com. in some time. She was very tense about studies…She was extremely clever and sharp. Her older sister was the highest educated and her aim was to get a degree even higher. She was always competing with her sister when it came to studies…I don’t know [why she would do this]. Only god knows. I don’t know anything more…If she had been alive, we would have gotten some answers. There was no tension at home. Maybe she just lost her mind for a minute and took this step…If her mother even had an idea of what was going on in her head, she would not have left her alone.”

Vandana is among the thousands of students who had their life and goals derailed by the pandemic. However, while her richer compatriots could afford to stay at home to bide away time wishing away the virus, for poorer students like Vandana, this lost time is precious and could be the pivot between success and failure, affluence and poverty. The matter becomes even more complex when considering the recent protests against holding the JEE and NEET exams due to the high risk of COVID transmissions in examination centers. We are faced with a conundrum: the exams themselves are a public health crisis, but not giving them has other human costs, as Vandana’s death demonstrates. With a lack of backup administrative and social infrastructure, we’re damned if we do, and damned if we don’t. Amidst this, reveals Amit, her cousin brother, “Everyone is under a lot of strain due to the coronavirus pandemic. She was also under a lot of stress, and couldn’t follow her dreams because of the pandemic, so she committed suicide. She wanted to get ahead in life, but she couldn’t get there… there are many other students in the same situation. People in the business world are also struggling. Farmers, especially, are the most affected. Everyone is struggling due to the pandemic.

Amit is right when he points to the plight of the farmers of our country. In the period between 1995 and 2015, a total of 321,428 farmers had committed suicide. Since then, the numbers have only risen. According to data collected by the PARI Network, renowned for working closely with rural populations across the country, on an average, more than 1000 farmers committed suicide in Maharashtra alone in the first 6 months of 2020. Yet, somehow our state and media deem an actor’s suicide more worthy of coverage and investigation than the steps thousands of farmers have been forced to take due to a plethora of disasters–natural, political, and policy-based.

Amit continues, “The only thing that has increased in the pandemic is the doctors’ salaries. Even the smallest things–When we ask for a bandage, they say, ‘we don’t have any!’ When we ask for injection, they write up a prescription for medicines we have to buy from outside. There’s literally nothing at the hospital. But the money, yes, that they always want on time…For starters, doctors don’t even do a check-up.

They never do it. Their first step is always to refer to people. The moment the person arrives at the hospital, the procedure to refer them to Chattarpur starts…Oh yes, definitely. If the doctor wanted, she could have been saved, because before bringing her to the hospital, we had made her vomit out the poison multiple times. It took us 15 minutes to get to Charkhari, because our village is 8 kilometers away. We did everything very fast, but the moment we arrived there, the doctor referred her to Mahoba. They didn’t even inject her with a glucose bottle. We had to ask for that from the medical staff. When we asked for the glucose bottle, they told us to buy it from the medical store in front of the hospital. After that, they referred to her. When I asked for an ambulance, they said it would only be available in an hour. The doctor said, “it’ll only take you 15 minutes, so drive your own vehicle.” When I mentioned it wasn’t my car, he said so, what? It’ll be quicker. He didn’t do anything to help…

She would have died there at the hospital if there was no car…if they wanted, they could have saved precious time and saved her there only.”

Clearly, then, in the absence of media coverage and government support, our nation’s medical infrastructure does not inspire confidence in the very people it is designed to serve. Perhaps, if we diverted our collective attention and resources to holding institutions accountable and providing networks of mental, financial, and emotional support in this quasi-apocalyptic time, we could be more confident of preventing people from taking drastic steps–whether they’re rich and famous, or not.

Written by Kaagni Harekal based on reporting and fieldwork by Suneeta Prajapati & Meera Devi for Khabar Lahariya. Watch the news report in Hindi here.