More than 50% of rural households are reported to have functional household tapwater connections under the Jal Jeevan Mission. But does this translate into availability of water for the rural poor?

Banda, Baghpat and Bengaluru : “We drink whatever quality water we can get,” says Munni Devi, a Dalit worker who lives in Banda district of Uttar Pradesh (UP). “Of course we get sick, but we don’t have any other choice. We are poor.”

On August 15, 2019, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led Union government announced the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) to provide a functional household tap connection (FHTC) to every rural household by 2024, thus ensuring potable drinking water for all.

“Mothers and sisters have to travel 2, 3, 5 km carrying the load of water on their heads. A large part of their lives is spent in struggling for water,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his Independence Day speech in 2019. “The central and the state governments will jointly work on this ‘Jal-Jeevan’ Mission. We have promised to spend more than Rs 3.5 lakh crores on this mission in the coming years.”

For Munni Devi, despite the government’s ambitious programme, the drudgery of accessing clean drinking water continues. The 40-year-old, living in UP’s backward Bundelkhand region, spends a few hours daily dealing with the uncertainties of collecting clean water, she said in April 2022, when Khabar Lahariya visited her village. Five months since, little has changed.

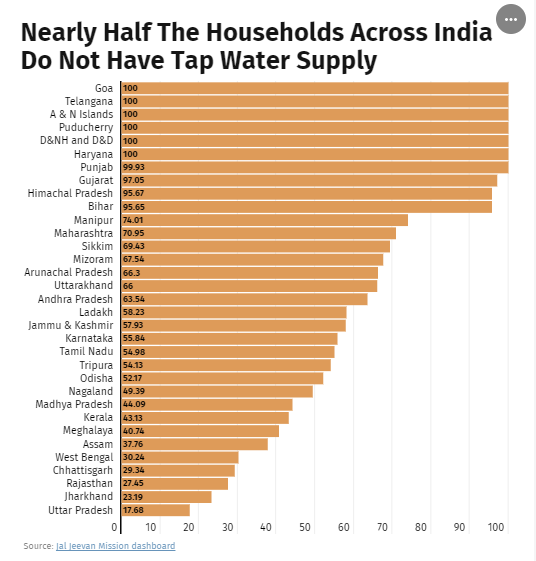

When the scheme was announced, only one in six rural households in India were reported to have tap water connections, according to the government’s JJM dashboard. By September 19, 2022, every other household had a new connection, an increase of 36 percentage points. Seven states and Union Territories–Goa, Haryana, Telangana, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Puducherry, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu and Punjab–reported 100% connections.

In UP, with a population of 199.8 million, 99% of households were reported to have basic drinking water service, and as many households used an improved source of drinking water, but only 14% have water piped into their dwelling, yard or plot, according to the fifth National Family Health Survey conducted between 2019 and 2021. Urban households in UP, with 36% coverage, are more likely than rural ones (7%) to have piped water.

Experts say the JJM scheme is important, but that the work was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as state elections in March 2022, and that the community needs to be more involved in taking decisions about the scheme at the local level. Further, the government should consider the local context, issues of availability of water and its quality in the scheme’s implementation.

In Munni Devi’s village of Pavaiya, where one in five persons are from the scheduled castes, not one of the 781 households had tap connections, according to JJM data accessed on September 19, 2022. “No one came here to inform us of the scheme,” said Munni Devi. “We came to know about it from TV, where Modiji said that through this scheme water tanks will be built and everyone will get water supply.”

Khabar Lahariya and IndiaSpend track the progress of JJM in Baghpat–with the most tap connections in UP at 48%–and in Banda, which has 17% household tap connections, similar to the state average.

Also Read : Women Farmers Are Losing Jobs, Earnings, Savings Even As Agriculture ‘Booms’

Many still depend just on one water source, a hand pump

Maya Devi, photographed in April 2022, is a brick kiln worker in Bamnauli. She has no functional tap connection at her house, and stores water for nearly three days.

In Bamnauli, in the northwestern district of Baghpat, 50 km from Delhi, Maya Devi, a Dalit brick kiln worker, has seen no change in the water quality for decades. “With no other option, we have to filter the water before consuming it,” Maya Devi said. “Very often, the water is dirty and has small insects floating around in it.”

Maya stores water in plastic containers for her six-member family. When Khabar Lahariya visited her home the water was three days old, with a thin film of dust and contaminants forming on top. “We fall ill because this is the water we drink–three members of my family are unwell right now. But no one listens to us, because we are poor,” said Maya Devi.

Water supply schemes have been part of post-Independence India since 1954, when the National Water Supply Programme was started. Over the decades, various schemes around water quantity and quality have been launched, including the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) in 2009-10, which has now been subsumed under the JJM. Even after spending 90% of Rs 89,956 crore ($11.5 billion) between 2012 to 2017, the NRDWP “failed” its targets, IndiaSpend reported in November 2018, based on the government auditor’s report.

Despite the efforts over several decades, around 43% of India’s rural households were dependent on hand pumps for drinking water as their principal source, according to the Drinking Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Housing Condition in India report of the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), conducted between July and December 2018.

In UP, 88% of rural households depended on handpumps for drinking water and 3% had piped drinking water source at home or in their plot, as per the NSSO report. Across India, 82% of rural households in India that used hand pumps as a principal source of drinking water did not have another supplementary water source. This proportion was as high as 94% in rural UP, second-most after Jammu and Kashmir.

IndiaSpend and Khabar Lahariya have reached out to senior officials of the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, and the UP government’s Namami Gange and Rural Water Supply Department for their comments on the progress of JJM, data-related clarifications, and challenges faced by the administration. We will update the story when we receive a response.

Progressive scheme, but 2024 deadline difficult to achieve

The JJM is a progressive water supply programme because it talks about water quality, participatory management, and securing water sources, but the 2024 deadline adds pressure, and financially, most states have to raise 50% of the funds, said Sunderrajan Krishnan, executive director of the Indian Natural Resource Economics and Management (INREM) Foundation. “It is complex, given the pandemic and governance challenges at the state level, such as hiring human resources, [engaging] civil society organisations, and skill building.”

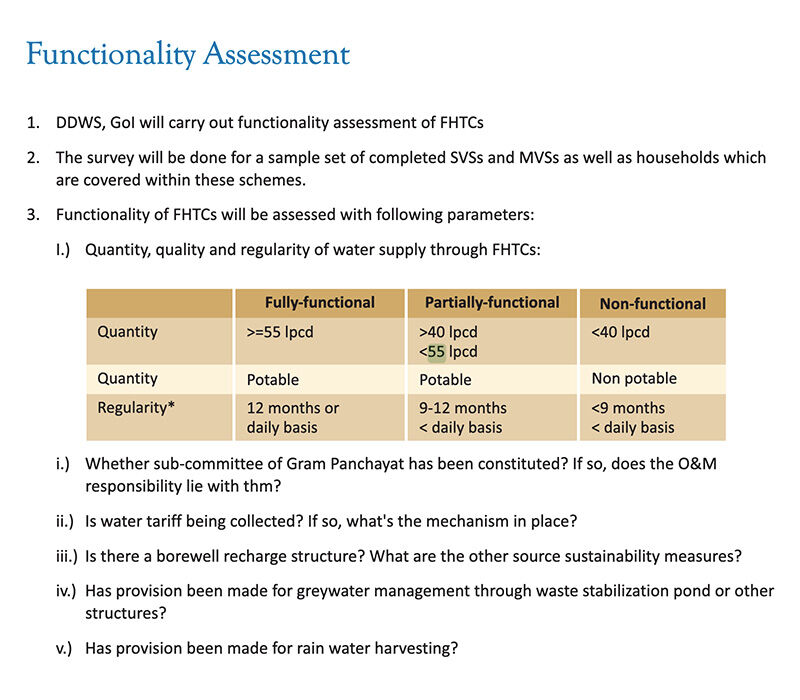

The JJM has various components, including funding coverage and water quality, bulk water transfers, treatment plants, retrofitting of completed and ongoing schemes to provide tap connections for at least 55 litres per capita per day (lpcd), water quality management and surveillance, tap connections to schools, anganwadis and health centres among others.

“The mission is quite popular in many areas of India, but questions remain on the sustainability of the mission, the involvement of communities and the quality of water provided,” said Neeha Susan Jacob, senior research associate at Accountability Initiative.

“Providing a piped water connection at a household level is relatively easy,” said Madhavan of WaterAid India. “But we will have to ensure that the source of water is sustainable, that the water is safe from contaminants, and there are robust mechanisms to ensure operation and maintenance.”

India is the world’s largest extractor of groundwater, and it forms a major source of supply for drinking water.

It is necessary to incorporate ‘source sustainability’ like balanced water extraction and usage, water quality monitoring and treatment, recharge of shallow and deep aquifers, catchment area protection and management, said Karthik Seshan, Manager (Programmes) at Azim Premji Foundation’s Philanthropy arm. “In the absence of these practices, JJM could potentially ensure taps in every household but without the desired levels of safety, sustainability and equity in water supply. The ambitious scheme runs the risk of having ensured Har Ghar Nal without Har Ghar Jal.”

Nearly 50 km northeast of Pavaiya, in the Khatan block of Banda, near the Yamuna river, JJM work was in full swing. Water is to be transferred from the river for at least 121 villages after it is treated in the water treatment plant 11 km away, in Kitahai.

Construction for transfer of water from the Yamuna river to 121 villages in Banda. Water will be treated before it is supplied to homes through JJM.

“Since we are taking water directly from the Yamuna river, the groundwater won’t be affected,” said Rajiv Vibhuti, quality manager of the Khatan water plan. “Yamuna river’s water here is drinkable and of good quality, unlike areas around Delhi, where it is of poor quality and not drinkable.”

Presently, these technical nuances do not translate into much for the expected beneficiaries, particularly women on whom the burden of fetching and collecting water falls disproportionately.

Munni Devi spends a few hours each afternoon hoping the solar pump installed in the village will work, so they can collect water. “Once it stops working, we have to make do with salty water from the handpump, and for additional needs people have to get private tankers.”

Maya Devi’s experience is equally troubling. The tap which was installed in her house more than two years ago does not work, forcing her or her children to fetch water from the village tank after her 12-hour gruelling workday. “If for some reason, we have more people over or there is a function at home, we end up spending Rs 500-1,000 on clean drinking water,” said Maya Devi.

Village representatives do not maintain the pipes, which leak and affect water availability, they complain.

“Our target is September 2022 to complete the work under the new schemes which fall under JJM,” said Rajendra Singh, Executive Engineer, Jal Nigam, Banda. Women are being trained so that they can test the water quality in their respective villages, the village panchayats are also training literate people on how to carry out basic repair work in case of water leakage, and how to operate a motor.

Khabar Lahariya has also reached out to Ramkesh Nishad, state minister for Jal Shakti and an elected member of the legislative assembly from Banda. We will update the story when we receive a response.

Passing the buck on slow implementation of JJM

In Baghpat’s Bamnauli, with a population of nearly 12,000, all households are reported to have tap connections but Ajay Kumar Tomar, principal representative of the pradhan’s (panchayat president) office says that a majority of households still do not get piped water, particularly homes of the poor and marginalised, like Maya Devi.

Water supply was provided to a few homes through schemes that were started in the 1980s, but over the years there have been disruptions, and around 70% of the homes do not have water supply, according to Tomar. The panchayat has informed the authorities officially about the lack of functional water supply connections, he said. “In spite of this, if someone says it is 100% FHTC, then it is a lie. While the government wants the work completed, officials are not able to do it.”

Tomar added that there are numerous leakages in the pipelines that were laid during previous local governments which were of bad quality. Despite repeated complaints, only a few have been fixed. Three major leakages were fixed through private contractors who charged Rs.5000 for each repair, he said.

Avinash Gupta, who was the executive engineer of Jal Nigam in Baghpat until April 2022, said that the panchayat has the responsibility to maintain infrastructure and fix pipelines that are old. The JJM work has only started, and none of the works have been completed, but water supply will begin soon in some villages, he said.

In 27 of 205 villages in Baghpat, pipes that are old will be relaid or replaced through the JJM. Of the remaining 178 villages, work has been approved in 84 and the infrastructure work, such as laying of pipes, has started in 70. “Presently, we are working on pumphouse and distribution, and tank designs have started to come in,” said Gupta. “The priority is to lay pipelines and start supplying water to at least 40 villages by the end of the year.”

On the ground, residents are unaware about the scheme. In financially well off communities in Baghpat that Khabar Lahariya visited, households were indifferent to the scheme as they had their own source of water, and money for submersibles to pump water.

Gupta said that the administration was encouraging participation of people through Implementation Support Agencies (ISAs), which inform communities about JJM. But ISAs have limitations and cannot visit villages on a daily basis to raise awareness, he added.

There is a need for a sustained campaign, not just in Uttar Pradesh but also in other states where a significant proportion of the population lacks access to household piped water connections, to make piped water connections aspirational, said Madhavan.

Also Read : The Kadar Community Charts An Inspirational Journey Of Resilience As They Take Back Their Forests

Underspending and inadequate fund allocation

The Union government had announced Rs 3.6 lakh crore for JJM, with fund-sharing between the states and the Union government, varying based on components of the scheme. States have to raise 50% of the funds for coverage on their own, though in the northeastern states the Union government will bear 90% of the financial costs. In the 2022-23 budget, the government allocated Rs 60,000 crore, a 33% increase over the revised budget for 2021-22.

But the allocation was only two-thirds of the Rs 91,258 crore demanded by the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, according to the Sixteenth Report on Demands for Grants of the Ministry of Jal Shakti by the Lok Sabha Standing Committee on Water Resources.

The JJM financial data report an allocation of Rs 92,309 crore for 2021-22 while the budget mentions a revised estimate of Rs 45,011 crore, a discrepancy that we have asked the government to comment on, and will update the story when they respond.

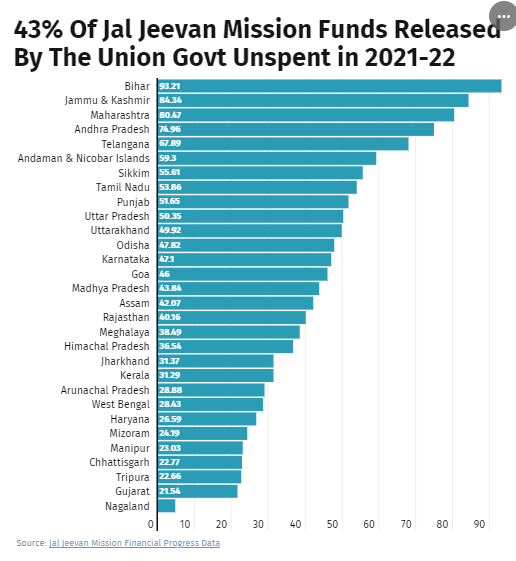

Further, in 2021, only 43% of the Rs 92,309 crore was released to states, and the programme reported more than Rs 19,000 crore of unspent funds–six times the budget for the mission for protection and empowerment for women. Uttar Pradesh had spent half of the Union government allocation in 2021-22, according to data.

In its recommendation, the standing committee on water resources said that it would “urge the Department to strive to utilise the allocated funds at the earliest so that they have sufficient justification to ask for additional funds at the RE [revised estimate] stage.”

The delays in spending occur for various reasons, according to a May 2022 analysis by Sidharth Santhosh & Neeha Jacob for Accountability Initiative. This includes delays in submitting fund utilisation certificates by states, or when states have large opening balances carried over from the previous financial year, or if states have their own drinking water supply schemes.

For example in Telangana, which has a Rs 46,000 crore Mission Bhagiratha to provide drinking water, fund withdrawal and utilisation gets complicated due to the state’s own allocation for a large water supply project. It is among the few states to report 100% FHTC. In 2021-22, Telangana “did not withdraw any funds allocated by the centre,” according to the analysis by the Accountability Initiative. The analysis said the state’s funds for Mission Bhagiratha were merged with that of JJM, and such cases can increase procedural complications and delays in fund disbursement and utilisation.

The Lok Sabha committee was “dismayed to note the underutilization”, and was concerned that the lack of financial discipline and prudence would “undoubtedly deprive the targeted beneficiaries’ access to safe and clean potable water at their homes”.

Also Read : From Print to Digital, 20 years of excellence

‘यदि आप हमको सपोर्ट करना चाहते है तो हमारी ग्रामीण नारीवादी स्वतंत्र पत्रकारिता का समर्थन करें और हमारे प्रोडक्ट KL हटके का सब्सक्रिप्शन लें’

Source :

Source :