Khabar Lahariya Managing Director and Co-Founder Disha Mullick writes on a peculiar case of medical apathy from the badlands, in a special article for Indian Quarterly

The last time Uma’s mother and I spent some time together, I swooned off her scooty on a blazing midsummer day, white fields spread out around me and not a soul in sight. We were reporting on the death by asphyxiation of a young woman in her husband’s home. Uma’s mother insisted it was murder.

And then, in January, I had had a similar experience of dizziness in her company, though in altered circumstances. I had followed a grimy, loopy, maddening trail that led me to the death of Uma’s 36-week-old foetus. This time, Uma’s mother was not the prime investigator but the investigated. Her daughter, just 20, yellow of eye and soles of feet distended, lightly covered with a sheet of flies in her mother’s aangan, had lost her first husband and her first child in the space of a year. Her second husband, the father of her first child, arrived in time for the burial, from work on a construction site in Delhi. He stood cautiously at the threshold of his mother-in-law’s house.

Uma’s mother smiled to see me in her home and then choked up over the fate of her eldest.

Watching Uma on her charpai, wearing my purple sweater, a woman failed by her state and by society, I couldn’t help but think of the upcoming general election. How stories like Uma’s go unnoticed while hundreds of hours are spent fanning the flames of jingoism, to take a recent example, under the guise of concern for national security. The issues that ‘matter’, as decided in Delhi television studios and news conferences, or on WhtasApp groups in our cities and kasbahs, take on a garish, pantomime quality.

I’ve known Uma’s mother for over seven years now. She came into Khabar Lahariya, the rural news channel I work with, as many other women do: unprepared for journalism, but prepared to do whatever she needed to survive in her world. Her story is numbingly similar to those of other colleagues: she is Dalit, she was married early, before she could complete her Class 5 exam, but she had the opportunity to attend a feminist residential programme for adult women in her district that would change her life. Well, in a manner of speaking.

Uma was six months old when her mother went to the centre to attend the programme. Her husband’s family, already hostile, told her that if she wanted to go away she must get more dowry from her parents, or else she could take her daughter with her and not return. Uma’s mother did some mental math, and concluded that attending the centre would enable her to complete her Class 5 exam and maybe get some work, that would make her less dependent on her unreliable husband. She decided to leave Uma with her parents while she was away studying. When she had a few days’ holiday during the course, she went back to her marital home but wasn’t allowed inside. She fought past her brother-in-law to get in, and told her husband (I imagine in her distinctive, not particularly aggressive but implacable style) that she would take what she was entitled to from him.

Over the years, this became a pattern in Uma’s mother’s life. She would steel herself to the whispers in her husband’s home that made it clear that she was an unwanted presence. Sometimes, she said, she would overhear them plotting to kill her; sometimes they restrained themselves to abuse directed at her and her family for their provision of ever-inadequate dowry. After she finished her six-month programme and came back to her husband’s home, his family sabotaged her job applications. When things became even worse, she left. But then she kept coming back, fuelled by the belief that this was her home too. Then she heard her husband and father-in-law plotting to burn her alive, and she locked herself in a room in the house and screamed so that the village would know that her in-laws were trying to kill her. Early the next morning, under the guise of going out to defecate, she made to leave her husband’s home. He saw her on her way out, and asked where she was going. “I’m going to the police,” said Uma’s mother.

She didn’t, but she got herself a room on rent, and worked as an agricultural labourer for some years, to support herself and her daughters. Her father, carrying the centuries-old burden of patriarchy—which she, swapping gender roles, would inherit—helped her with food and money. He asked her to come home: “When he doesn’t let you stay with him then why don’t you live here? And if he doesn’t come around, we’ll file a case against him.” But his stubborn daughter, luckless in love, preferred to live independently. She took legal help from a women’s group and eventually filed suit against her husband for dowry harassment. The case languished in the courts for over a decade until Uma’s mother withdrew it.

In 2011, she applied for a job as a reporter with Khabar Lahariya, at the time a newspaper published in such local languages as Bundeli and Avadi. Her limited literacy, bad marriage and debilitating finances, added to a natural curiosity and relentlessness, meant she was ready to do what it took to get the job done. Three years later, reporting on the general election, Uma’s mother was gheraoed by a group of Thakur men, when she was selling copies of the newspaper in a village close to her home. The front page of the issue featured a story about Mayawati, and what her constituency felt about her chances. This, for the so-called upper caste men, was enough proof that Uma’s mother, a Dalit, and therefore a Bahujan Samaj Party supporter, was campaigning for the BSP. They took all the copies she had, snatched her camera away, and refused to let her leave. Uma’s mother, no stranger to intimidation and attempted assault, managed to get herself home.

Later, though, at the local police station trying to file a complaint in a roomful of dismissive Thakur cops, it was clear they thought she had it coming to her. That she, a woman and a Dalit, was being uppity. Uma’s mother was astute enough to return later with a colleague from the paper and make sure her complaint was filed.

Only three or four years after she began working at Khabar Lahariya, cognisant that her husband was unlikely to ever pay to support her and their children’s futures, Uma’s mother bought a piece of land in her own name. In 2017, when Uma was about 17, and had failed her Class 12 exam, her mother—who was already substantially supporting her ageing parents as well as the younger children—decided it was time to bite the bullet and marry Uma off. She found a groom, made all the arrangements, and prepared to give her away. She sent her husband’s family a cursory invitation, not expecting they would care.

But you know what they say about bad pennies.

On the eve of the wedding, a large party from her husband’s side of the family turned up at the venue, and convinced Uma’s mother that it wasn’t auspicious to have a wedding without the ceremony in which the father gives the daughter away. They’d be persuaded to do it, they said, if Uma’s mother dropped the case she had filed against her husband, and the claims for a maintenance stipend. Uma’s mother, ever the pragmatist, agreed.

Uma, a fly in a web, always aware of being one among her mother’s many burdens, always unwanted by her father, found love and happiness, unanticipated, in her first year of marriage. Barely did she begin to recognise what this felt like, when her husband, also a migrant labourer, committed suicide, allegedly due to a quarrel with his father about how Uma was treated while he was away for work.

Back to her maternal grandparents’ home, and her taut mother, Uma’s brief youth faded. Her father’s family insisted that Uma be remarried soon; Uma’s mother succumbed to the pressure while Uma withdrew into herself, unable to find the mental strength to resist. She was married off again, this time to a distant relative from a village in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh. Her new husband, a sweet, quiet man in his mid-twenties, had worked more than half his life on various construction sites in Nangloi, West Delhi, and spent the better part of the year away from home. In his absence, Uma’s in-laws couldn’t be bothered to maintain a charade of care or concern. When her husband left for work, barely weeks after their marriage, she returned to her mother’s. Only a few weeks later, still pining for her first husband, she tried to kill herself, using the same agricultural pesticide with which he had poisoned himself.

Momentarily, both sides of the family paid her some overdue attention. Her husband returned from work for a few days. Uma was still grieving, still weak. And, it turned out, she was pregnant.

Our lives are a tangle of many threads. The fabric of Uma’s mother’s life may have been mostly faded, may have been wearing thin, but patches were still bright. Her professional life, whatever the turmoil in her family life, was greatly enriched after the 2014 elections, the 2015 panchayat elections in UP and the 2017 UP assembly elections. She had fought for personhood in every aspect of her life—for education, for respect in and outside of her marriage, for financial security, for respite from physical violence, for entitlements from the state as a single, scheduled caste woman. Taunted for the slow speed of her note taking when she began her life as a reporter, Uma’s mother was now a fixture at police stations and dogged in her pursuit of corrupt local leaders, unafraid of their links to the mining mafia. She had bought a second-hand scooty, learned to do video reporting on her new smartphone, and become a regular at the mobile repair shop at the head of the Tindwari block market. Uma’s mother had turned herself into a confident, disruptive, political exponent of digital journalism, the contrast with her domestic conditions and status stark.

Perhaps where her personal and professional lives did intersect were in the stories Uma’s mother proved most adept at covering—exposés of violent crimes committed on women that are then hushed up or ‘settled’ by families. For instance, in the case of the death of two young daughters-in-law, residents of adjacent villages of Tindwari block, one allegedly by asphyxiation, the other by poisoning. Uma’s mother was crystal clear in her mind that these were cases of murder by the families, and diligently put together evidence, including detailed interviews with family members and neighbours. She examined photos of the bodies marked with injuries, pointing out the elisions in the postmortem reports that described the deaths as accidents. Compared to a reporter on a mainstream newspaper, even if a provincial one, Uma’s mother was familiar with being on the margins, with not having a voice. She understood the families’ silences, was intimate with the connections within each household and the structures of power, and was non-confrontational despite her doggedness. Such intimacy led to powerful, unique and sometimes scathing reportage.

This combination of confident journalist and marginal citizen worked on paper. In life, though, as Uma’s mother discovered in January, it meant her daughter being refused care from the public healthcare system in the last stages of her pregnancy. When I heard the details from a colleague—who was with Uma’s mother all through the harrowing day and night that she lost her grandchild and had to go alone to bury the stillborn foetus—I said (in a momentary lapse of professional detachment) that we owed it to Uma’s mother to escalate the reporting of this tragedy as far as we could. But when we went to see Uma and her mother, the former was swollen and jaundiced and entirely indifferent to our furies. Her mother was nervous and uncertain, haunted by guilt, grief and fear of what was to come. She was also clear that she had to report in the district for the next general election, and it was best that she didn’t ruffle too many local feathers with an antagonistic story. So we promised to blur her broken face and voice, as we recorded her experience of callous negligence.

Makar Sankranti, more popularly known as Khichdi in Uttar Pradesh, fell on January 15 this year, a day later than usual. So when, after a few days of abdominal pain, Uma couldn’t bear it anymore, her mother didn’t stop to think of it being a significant holiday. She took her daughter to the first point of call in the rural healthcare structure, the ‘sub-centre’ in Chilla town, 30 kilometres away, where Uma had been going for injections over the duration of her pregnancy. They were told by the nurse there, after a cursory check-up, to go to a higher level hospital for blood tests and that the delivery was still three days away. When we went to the same sub-centre a week later, with Uma’s mother, who kept out of sight while we went inside, it was bathed in sunlight and scattered bougainvillea, and deserted except for the auxiliary nurse midwife’s gnarled mother. The ANM told us over the phone that she had been suspended three months ago (over the dubious death of an infant) and so was not on duty when Uma was brought there that day.

After being told to take Uma for blood tests, her mother hired a private vehicle, after losing patience with the process of calling for an ambulance (she had to explain to a call centre in Lucknow how to get to Padaratpur in Banda) to take them to the Emergency ward at the district hospital. Once there, the doctors referred her to the women’s hospital next door. “We can’t handle deliveries in the emergency ward,” explained Dr Vipin Sachan, on duty in the Emergency ward at the time, “We are all men.” At the women’s hospital, the staff, after looking at the ultrasound report told Uma and her mother that the doctor had left for the day, and they should go elsewhere. The hospital staff claimed they didn’t have the facilities to admit her there. They also said the foetus would be ejected by the body within 48-72 hours.

Uma’s stillborn child was delivered hours later in a private clinic. The treatment cost over 30,000 rupees.

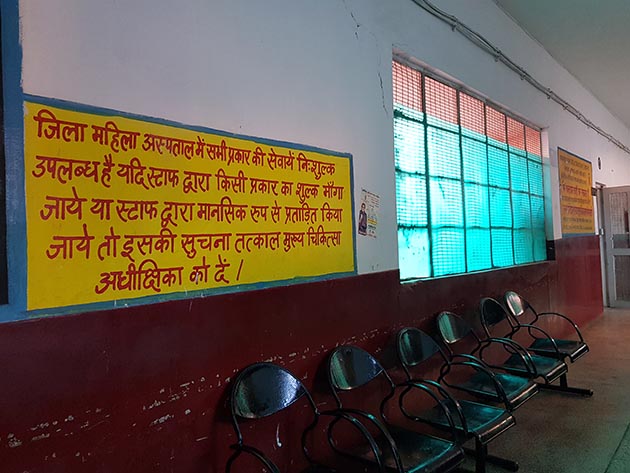

Uma’s mother giving an interview on Uma’s experience with childbirth in the government healthcare system | Khabar Lahariya

In the weeks following this incident—scarring, yet somehow unextraordinary—I had many conversations with Uma’s mother around personal and professional decisions I thought she should consider. At the time of completing this piece, Uma is recovering, her jaundice reduced, the ability to take a selfie on her mother’s scooty restored. While reporting on the piece, we had spoken to the Chief Medical Officer in Banda who said he expected Uma’s mother to file an official complaint against the district women’s hospital at the way her case was treated. Uma’s mother dismisses this with a trademark laugh, light, yet harsh. “She’s fine now, what’s the point of a complaint?” Then she spoke more freely than she had yet, about the dubious role played by the midwife in her region, under whose watch three cases of death by negligence, or inadequate medical knowledge, had occurred.

Uma’s mother had reported these cases over the last couple of years. Still, she’s wary of the midwife. She reportedly asks for money from patients to perform deliveries, a service that should be free. In this case, as in most cases involving reporting on corruption in public services, local reporters are paid off by local grandees to look the other way. “It’s easier to put pressure on me,” Uma’s mother says, “because I’m from a lower caste.” She’s already been under fire for several months for her reporting on toilets being hurriedly installed in preparation for the elections, and electricity meters, equally hurriedly installed, that produce bills though there is no power. Uma’s mother is earning a reputation for being a particularly annoying fly in the works.

As a close observer of Uma’s mother, and someone who is now implicated in the trajectory of her life, I don’t think she ever saw her work as a reporter as a means to set right an askew world. But I do think her journalism has heightened her sense of self and what is necessary to negotiate that self in her space—her home, her village, her district. She knows that her journalistic ‘voice’ poses risks, that while there is power in being a reporter it doesn’t remove her entirely from her society. In some ways, she is even more deeply enmeshed. Uma’s mother manages to report both from the inside and the outside. Her position on the margins dictates both the kinds of stories she wants to tell and her responses to events. She is helping to redefine what it means to be a reporter. A fact that she can’t help but be aware of when she’s out on a story and there’s hardly ever another reporter with her caste and class background, who shares a similar address.

Uma’s mother is poor, rural, and Dalit but she has the right to ask questions. She now knows that the government, society, owes her answers. Whether those with the power choose to fufil those obligations is another question, one we should be asking at every election.