If you’ve been following along, you’ve heard from journalists, fact-checkers, and communities navigating hostile digital spaces. If you’re just joining us, catch up on our previous dispatches: field reporting from rural India on why gendered misinformation spreads so quickly, video podcast with urban and rural women about their digital lives, and interviews with Pallavi Pundir, Rohini Lakshané, and Yesha Tshering Paul on state impunity, political machinery, and how disinformation erodes trust in the margins.

As the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence conclude today, this year’s theme- “End digital violence against all women and girls” speaks directly to the urgent questions we’ve explored throughout this series: how do we build digital spaces where women and marginalized communities can exist without fear, harassment, or coordinated attacks?In this final piece, we explore what it takes to build digital infrastructures that actively center women’s safety and agency not as an afterthought, but as a foundation.

Over the past decade, the idea of ‘feminist infrastructure’ has slowly entered conversations around gender justice and digital rights. But what does this term really mean especially in India’s rapidly evolving online ecosystem?

At its core, feminist infrastructure refers to digital systems and platforms intentionally designed with an ethic of care, prioritizing inclusion, safety, and agency for marginalized communities such as women, queer people, and persons with disabilities. It goes beyond mere technology or tools: it is a political commitment to ensure that those most vulnerable to marginalisation and online harm also shape and influence how digital spaces function.

The gendered digital divide remains stark in India. As of late 2022, women accounted for just one-third of all internet users nationally. According to the IAMAI–Kantar Internet in India Report 2024, even though rural India now has nearly 58% internet penetration, only about 47% of women have ever used the internet, compared to nearly 53% of men. The gender gap widens when it comes to ownership and autonomy: although about 76% of rural women use a mobile phone, only about 48% actually own one as per the findings from Comprehensive Modular Survey: Telecom between January and March, 2025; highlighting a major discrepancy in digital privacy and control. Meanwhile, active female internet users in rural India have grown by 61% since 2019, yet women still trail men in ownership and digital literacy.

“For us as researchers and co-authors of the report, the term infrastructure is inherently political. It is determined by structures of power and privilege,” Sneha explains. Puthiya Purayil Sneha, a researcher with the Open Knowledge Initiatives programme, IIT-Hyderabad works in the areas of digital cultures and open knowledge, and has an active interest in gender and digital rights. She previously worked with the Centre for Internet and Society, where she also had the opportunity to engage with work on gendered information disorder, and larger discussions on feminist, inclusive internets. In this conversation, she unpacks how feminist digital infrastructures function not just as tech solutions, but as political commitments to inclusion, care, and resistance particularly in the face of rising gendered disinformation and organised online hate.

“A feminist infrastructure, then, is one that is inclusive, accessible, and developed with an ethic of care.”

She remembers coming across the term first around 2014, when organisations like APC (Association for Progressive Communications) began talking about “feminist principles of the internet” , a set of guidelines that “offer a gender and sexual rights lens on critical internet-related rights.” These ideas served as a springboard for her work on feminist infrastructures at CIS, where she co-authored a report with her colleague Saumyaa Naidu delving into feminist publishing in digital spaces.

Why Feminist Platforms Struggle to Sustain

Through interviews with feminist publishers, content creators, and rights organisations, Sneha and her co-author found two core challenges when it comes to setting up and continuing the work of feminist platforms: safety and sustainability.

“It’s unfortunate,” she says, “as observed by one of the publishers we spoke with in this study, that even today most writing about women and technology, or even women and queer folks wanting to engage meaningfully with technology, is inevitably about safety.”

Women in this Meedan supported study explained how digital exposure triggers real fear. One young social worker described receiving unsolicited photos and intrusive remarks on Facebook. Others reported community policing of their online presence as comments on late-night activity, sharing or photographing their daughters to shame them, or manipulated images posted locally to discredit their reputations. These experiences illustrate how gendered disinformation turns digital tools into sources of social surveillance, driving women to self-censor and withdraw from online spaces entirely

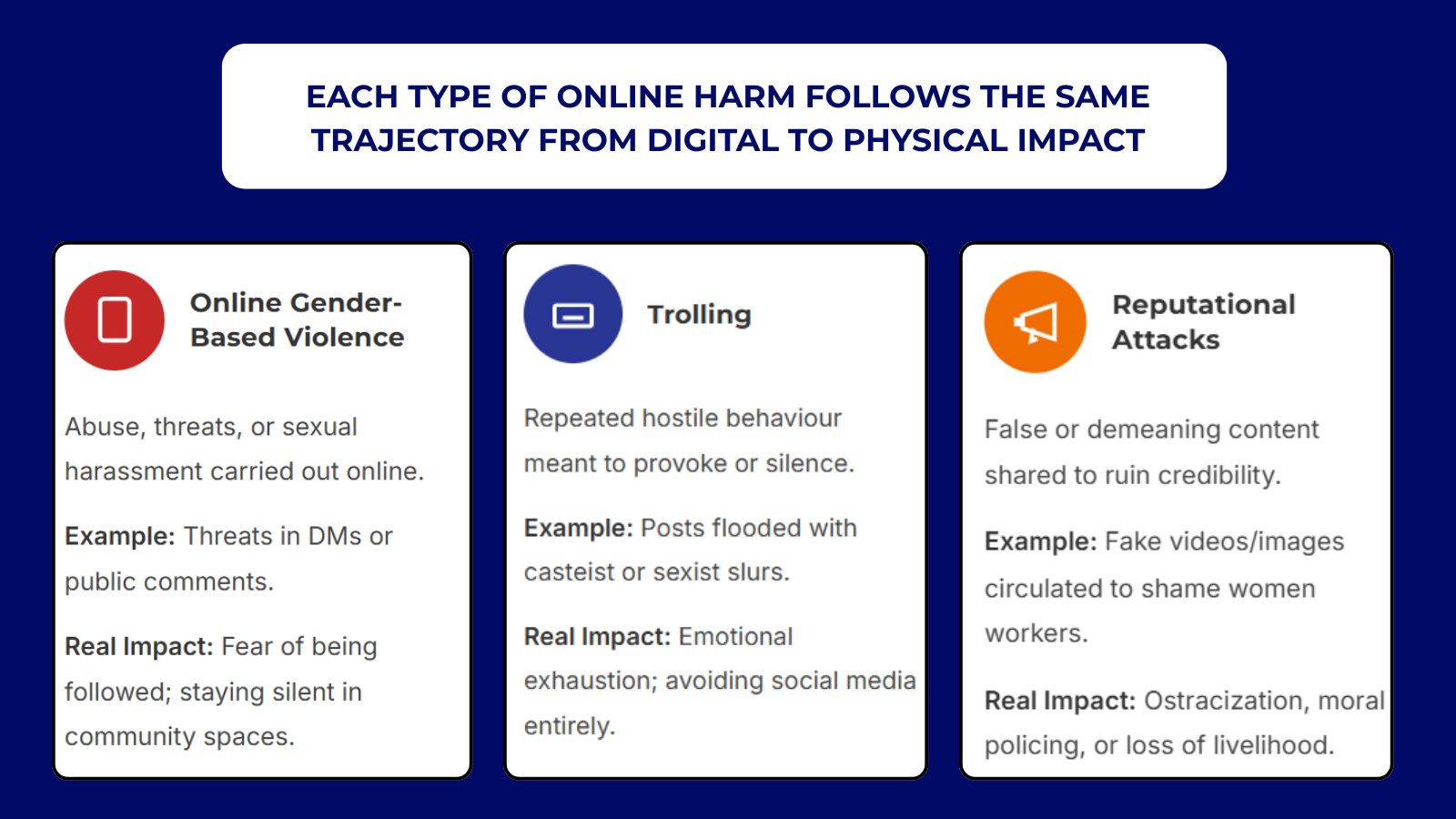

Online gender-based violence, trolling, and reputational attacks remain common, especially for those working at intersections of caste, religion, and sexuality. Many respondents shared how their safety concerns extend offline too, often affecting the physical location of workspaces and public engagement.

Different Forms of Tech-Facilitated Gendered Harm

The Harvard Misinformation Review has recently reframed this as a form of gendered violence, arguing that gendered disinformation should be recognised not merely as a speech issue, but as a deliberate tactic to reinforce patriarchal power, limit agency, and erase women and gender-diverse people from public discourse. This conceptual shift matters, it locates disinformation within the continuum of structural and societal violence.

Akanksha Ahluwalia, who leads social inclusion, media information literacy, and communication-driven programmes at the Digital Empowerment Foundation, has witnessed this violence firsthand in her field work. “Our work on digital disinformation began when we realised that communities we serve, especially rural women, elders, and first-time internet users were repeatedly acting on misleading posts without having the tools to verify them,” she explains. “Field teams kept encountering cases where people were forwarding religious hoaxes, falling for online job scams, or believing rumours that directly endangered women. One woman in Maharashtra, for instance, was nearly subjected to a witch-hunt because viral posts portrayed her as someone who steals children. In Jharkhand, a rumour linked to the Jan Dhan Yojana pushed hundreds of women to break COVID protocols and queue outside banks out of fear that their money would be taken back. These incidents made it clear that misinformation isn’t just an ‘online problem’ it produces real physical harm, panic, and gender-targeted stigma.”

In response, the organisation built disinformation awareness directly into their digital-literacy work. “Our focus is on safeguarding communities and helping them navigate a digital world where misleading information spreads much faster than correct information and where women are disproportionately targeted,” Ahluwalia adds.

The second barrier is long-term sustainability. Most feminist media and rights-based platforms in India are “labours of love,” driven by a small number of people, often without steady funding or institutional backing. As Sneha notes, “as publishers and editors interviewed in our study also highlight, stories on women, gender and sexuality are often classified as ‘soft content’. It’s not viewed as urgent as, say, a financial scam or political crisis.” This impacts interest and funding available to support the work of independent feminist platforms.

This also foregrounds another challenge, that of visibility of feminist stories. Algorithms rarely prioritise such content, and social media platforms with their opaque and ever-changing systems- don’t make things easier. A recent Meta-supported study pointed out that automated systems frequently fail to identify coordinated misogynistic campaigns, especially in non-English content from the Global South. This makes it harder for feminist platforms, especially those operating in Indian languages or regional contexts, to gain traction or protection online.

From TikTok Bans to the Manosphere: What’s Changed Online?

Digital spaces have changed in recent years, especially with developments like the ban on platforms like TikTok, which previously enabled women from non-metropolitan areas to build content, income, and visibility. In contrast, platforms like Instagram often feel like a black box, with ever-shifting rules and little clarity on what works. Simultaneously, threats to freedom of expression have grown more organised and ideological.

“The rise of networks like the manosphere and incel culture is deeply worrying,” observes Sneha. “Mis/disinformation isn’t just sporadic anymore. It is strategic, well-resourced, and often politically aligned.”

She cites reports from organisations like Amnesty on the targeting of women politicians, noting how hate campaigns intensify during elections. Social media, once celebrated for enabling democratic mobilisation, is now also enabling coordinated attacks against gender rights. Research from CIS reveals how gendered disinformation functions strategically to diminish women’s political participation and public influence. Social media, once celebrated for enabling democratic mobilisation, is now also enabling coordinated attacks against gender rights.

Analysts from EU DisinfoLab and the Brookings have confirmed that gendered disinformation networks often align with far-right or nationalist groups, where digital hate is both ideological and operational. These networks don’t simply troll, they conduct multi-platform, multilingual attacks designed to create distrust, degrade credibility, and suppress participation, particularly around elections.

This is compounded by regressive content moderation policies. Global tech platforms often lack the linguistic or cultural nuance to understand content in Indian languages, let alone slurs, satire, or codes used to harass women or marginalised groups.

Internal documents from the Wall Street Journal’s “Facebook Files”, based on whistleblower Frances Haugen’s disclosures, reveal that Meta lacked effective classifiers for Hindi and Bengali, two widely spoken Indian languages. As a result, much antisocial content, including hate speech and misinformation in these languages, went unchecked or was inadequately addressed

As the whistleblower noted, while 90% of Facebook’s users are outside the U.S., including large numbers in India, the platform’s AI moderation systems struggled to deal with non‑English content, resulting in significantly less moderation in regions like rural India compared to the Global North.

“Language isn’t just a translation problem; it’s cultural. If you remove third-party fact-checking or don’t work on updating content moderation standards, you open up the space to mis/disinformation and hate, especially in countries in the global south where the diversity of linguistic and cultural contexts don’t align with existing Western-centric policies.”

As per a Cambridge study, Meta’s content moderation practices reveal a stark global asymmetry, with India facing disproportionately low reviewer-to-user ratios, inadequate detection in regional languages, and minimal engagement with civil society. These systemic gaps enable gendered disinformation and other harmful content to thrive unchecked in the Global South.

The Rise of Rights-Based Discourse Despite It All

Still, Sneha sees cause for cautious optimism. “A heartening point observed by one of our interviewees in the report was that in the past five years, there has also been a visible rise in rights-based discourse on social media. People have created spaces for feminist and anti-caste conversations on social media, even when the platforms may not necessarily support it.”

She sees hope for such continuing discourse in early community-led models like Dalit Camera and Dalit Art Archive, and in emerging design justice conversations in India.

This growth, she acknowledges, is now under threat. But it also proves that feminist resistance is not just reactive, it’s creative, adaptive, and community-driven.

Gehrke and Amit‑Danhi argue that we must treat gendered disinformation as systemic identity‑based violence, not just isolated misinformation. Their “triangle of violence” framework like mapping content creators, victims, and audiences offers a tool to analyze how harmful narratives circulate and persist, and to design proactive strategies that disrupt these cycles before reputational damage and exclusion occur.

The Global Partnership Statement warns that gendered disinformation undermines democracy when it silences diverse voices, and urges states and platforms to adopt a Rights‑by‑Design or Safety‑by‑Design approach that protects women, girls, and LGBTQI+ individuals across the Global South and beyond.

Disinformation as Gendered Violence

Gendered disinformation, Sneha suggests, is not a separate issue but one deeply woven into the digital experience of marginalised communities. Its impact is far more than informational; it is emotional, reputational, and often deeply unsettling.

While her research on feminist infrastructures didn’t directly focus on it, Sneha says the overlaps are clear. Misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (content designed to harm) are increasingly used as tools of online gender-based violence.

“Look at the kind of reputational harm women journalists and politicians face due to gendered mis/disinformation,” she says. “The intent behind disinformation is often the same: to silence, discredit, and deny access to platforms.”

This is especially true for women and queer folks who work at the intersections of identity and power. “If you’re talking about caste, gender, sexuality, religion and/or their intersections there is always a concern about targeted gendered mis/disinformation.”

Sneha also cautions that the typical response to mis/disinformation i.e. increasing users’ digital literacy often shifts responsibility onto the very people being harmed. “We’re told to become more discerning, to build awareness, to fact-check everything we see. But not everyone has the capacity to do that. My parents, for instance, didn’t grow up with these technologies. Yet they are now on WhatsApp, receiving a barrage of false health advice and financial misinformation,” she says.

A 2024 report by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) argues that most counter-disinformation policies fail to account for intersectional harms, instead relying on broad community standards that do little to protect marginalised women.

Rethinking Allyship: Tech, Funders, and Design Justice

How, then, do we rethink allyship within feminist digital infrastructure?

Sneha believes allyship is about supporting without taking over. “If you are not from a marginalised community the objective is to centre the voices of those who are, in these conversations around technology and tech-building.“ A relevant principle here is that of “nothing about us, without us”, from the disability rights movement, which needs to become more prominent in the discussion around design and deployment of new technologies.

Feminist infrastructures, in this view, aren’t just about making platforms “nicer” for women. They are about redistributing power, prioritising care, and embedding inclusivity from the ground up in code, in policy, in funding, and in intention.

For Sneha, this redistribution of power must also include recognising the emotional and logistical labour required to support people harmed by gendered mis/disinformation and online violence. “Where are the support systems for people who have been targeted? Most often, it is under-resourced feminist nonprofits and digital rights groups doing the work. They are the ones manning helplines, offering care, and holding space for survivors. That labour is exhausting, and it’s largely invisible.”

Gendered mis/disinformation therefore requires a more holistic approach, one that doesn’t isolate it as a content problem but sees it as a safety crisis, a governance failure, and an emotional burden especially for those at the receiving end of targeted harm. It also demands a more nuanced understanding of digital infrastructures with their gendered dimensions, and well thought out strategies to make them more inclusive and accessible to all.

This dispatch concludes our gendered disinformation series, a collaboration between Chambal Media and the Association for Progressive Communications (APC). Through field reporting, interviews, and community conversations, we’ve traced how disinformation functions as systematic gendered violence and not just as isolated “fake news”.

The challenges are clear: algorithmic opacity, under-resourced feminist platforms, coordinated hate networks, and content moderation systems that fail the Global South. But so are the solutions: community-led digital literacy, intersectional fact-checking, platforms built on care rather than extraction, and movements demanding accountability from tech companies.

Feminist digital infrastructures aren’t abstract ideals. They’re practical necessities being built by those who know that access without safety isn’t liberation. The question now is whether we have the collective courage to demand, fund, and protect them.

The work continues and it requires all of us.

Credits:

Report and Written by: Sejal

Edit: Srishti

यदि आप हमको सपोर्ट करना चाहते है तो हमारी ग्रामीण नारीवादी स्वतंत्र पत्रकारिता का समर्थन करें और हमारे प्रोडक्ट KL हटके का सब्सक्रिप्शन लें’